Essay

Lockdown Diaries: A Day In The Life Of Anukrti Upadhyay

I am not a morning person. I like reading and writing late into the night, and waking up early in the morning has always been a chore. However, these days, no matter when I go to bed, I invariably wake up between 6.00 am and 7.00 am.

Some days I lie in bed, listening to the birds – the fluty bulbuls, the anklet-like sunbirds, and the crazy cuckoo who begins singing of his heartbreak with the first ray of the sun. On other days, I get up and sit by my window, breathe in the cool morning air, and watch the sky and the tops of the trees brighten, moment by moment. I concentrate on the beauty around me and try to push away the uncertainties and anxieties of these times, the baffled sorrow at the miseries unfolding all around, the ever-present guilt of privilege, and the utter powerlessness to change anything. I turn over the pages of Death In Midsummer by Yukio Mishima and read the story of the woman who lost a pearl on her birthday while the morning sky turns from pearly to golden.

I separate the days that threaten to fuse into one another by the dishes I cook or plan to cook. I move the house plants to sunny spots and then move them back when the afternoon sun slants in. I air out all my cupboards and open all the windows to let the outdoors in.

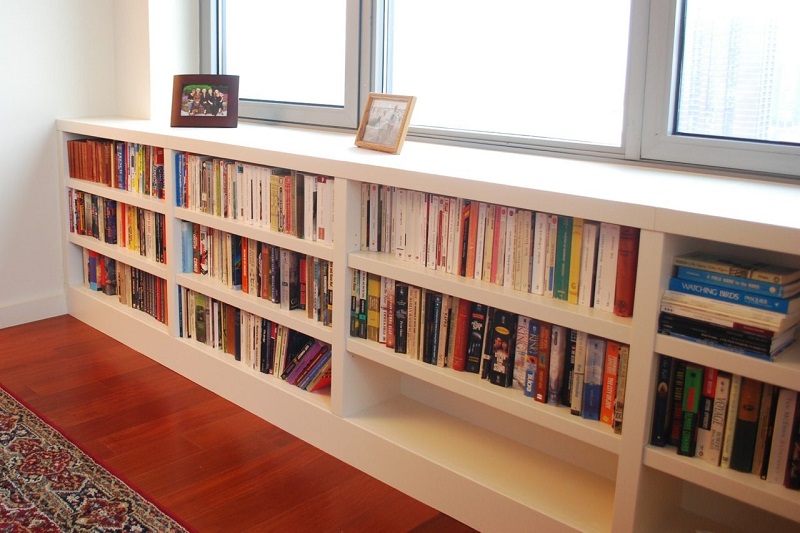

I go through my bookshelves and make lists of books to re-read. I write odd pieces at odd times – an epilogue to an already published novel, strange stories which unfold in dream-like montages that are alternatingly sharp and vague, snatches of poetry. I switch between pieces of writing, not restlessly, but more like a boat slipping downstream.

I watch the cat settle under the shade of stationary cars in my building’s parking lot. I listen to the sound of a solitary broom sweeping the driveway. I wave to my neighbours’ children as they press up against the glass of the large picture window and look out at the green lawn, dappled with shade and fallen sun-yellow leaves. I can no longer play with them on the grass, amidst the sprinklers. I mutely point out the large kite’s nest high up in the crook of a Gulmohar tree to them and see them gesture back animatedly.

I try to not let the petty concerns of my life under lockdown occupy all my conscious thoughts – grocery lists, a faulty water purifier, a water heater that doesn’t work and a leaky sink. I hug my son; I speak to my husband over video call and show him the brilliant blue of the sky. I call up family members scattered across cities in India and abroad. I talk about ordinary things, lunch and dinner menus, recipes and memories. I crack jokes about emerging from this lockdown with messy eyebrows and unkempt hair. I try to keep my face smooth and opaque, and not allow it to reflect the fears and anxieties I constantly feel.

(Image via Firstpost)

I devour all the news and information on my social media newsfeeds. I carefully avoid the statistics of the sick and the dead, choosing to only focus on the people. The people who are suffering and are real, their spouses, parents, children, neighbours, friends – all of whom have been drawn into the invisible and deadly net of this rampaging microbe.

I read about those who are desperate to reach the homes they had left so eagerly to escape poverty and hunger. Now they want to go back to those same homes, so that if death comes, they would at least be among familiar faces.

I arrange for grocery packets to be distributed at a slum nearby. I am told that the children asked for biscuits there, the adults for pickles, and everyone for hand sanitisers. I ring up my friends and acquaintances to source the goods. I feel exhausted with the needs and the scarcity all around. For a short while, I retreat to the lush, lost world of Junichiro Tanizaki’s Makioka Sisters, and lose myself in pre-war Japan.

My WhatsApp chat groups are filled with conspiracy theories blaming this political party or that community, with hate, fake cures, holy chants, jokes, photographs of sunsets. People are still trying to prove points and settle scores. Unquestioning allegiance and uncritical support are still being demanded over social media. Irrational symbolism and vague assurances are still being pedalled. A sickness of minds is raging, just like the pandemic.

(Image via Pinterest)

I feel anger and frustration form like a mass in my chest, and I feel it rising up my throat. It tastes like cold steel. I put away my phone and laptop and pick up the Palm-Of-The-Hand Stories by Yasunari Kawabata. I let the slow, enigmatic charm of his pared-down, rubbed-out, condensed stories engulf me.

At night, I hear the bats rustle and shuffle among the leaf-laden branches of the trees. Owls screech and swoop and the cats hunt in the flowerbeds in the garden. The back lane, where lovers come to make up after a quarrel and domestic helpers from nearby buildings resolve family disputes over long-distance phone calls and children chase after each other on summer nights like these, is silent. The lovers are practicing social distancing, the domestic helpers have retreated to their villages and the children are locked indoors.

I lean out of my window and try to spot the moon, and then remember that it is the dark phase. I turn back to Tanizaki Sensei’s Seven Japanese Tales and read about the blind shamisen player, the diabolical tattooist, the kleptomaniac, the blind masseur, and the man addicted to a woman. Silently, all of them step out of the book and crowd my lonely night.

Anukrti Upadhyay

Anukrti Upadhyay writes fiction and poetry in both English and Hindi. Japani Sarai, a collection of Hindi short stories and two English novellas, Daura and Bhaunri, have been published to date, and a number of works are in progress. Her short stories have appeared in numerous prestigious literary journals. With post-graduate degrees in Management and Literature and a graduate degree in Law, she also wrote a doctoral thesis on Hindi Literature. She divides her time between Bombay and Singapore.

You can read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!