Essay

Why Chetan Bhagat’s One Indian Girl Is Anything But Feminist

Kerry Harwin

March 23, 2018

When the head honchos at The Curious Reader gave me the green light for We Read The Bestsellers So You Don’t Have To, there was no question who would inaugurate the series. To curious readers, Chetan Bhagat is often used as a punchline. But I never made that punchline, because I had never read the man’s work.

One Indian Girl, the author’s most recent smash, is Bhagat’s attempt to write a feminist novel. The book follows Radhika, a 28-year-old high-flying Goldman Sachs VP from Delhi. We first meet her as her family arrives at a Goa resort for her (arranged) destination wedding.

Radhika, always the good girl, the school topper, always ashamed because she lacked the looks of her fairer, more social sister, manages to secure an Associate position at Goldman Sachs in New York. In her first week in the city, she succumbs to the desires of every frustrated Indian woman who has just moved to America: she immediately begins a relationship with Debu, a nerdy, kurta wearing Bengali ad-agency creative. From the moment he tells her that he’s going to “go down there”, in what may qualify as one of literature’s most ham-fisted sex scenes, she’s hooked; smitten by the fact that anyone might find her attractive.

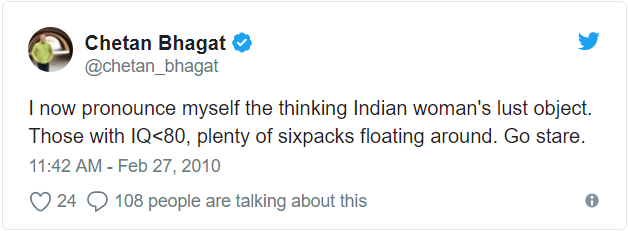

Of course, throughout her courtship and throughout the novel, Radhika can’t seem to escape the feeling of being a “slut”, a debate we witness through the protagonist’s awkward italicized internal monologue. It feels like Chetan got the message that a woman who has sex before marriage isn’t necessarily a “slut”, but his feminism is still lagging a wave or two behind. Janet Hardy’s The Ethical Slut came out more than a decade ago, but Bhagat hasn’t learnt that it needn’t be a bad word. But as Bhagat writes in the novel’s Acknowledgements section, his research process involved not, you know, books, but interviewing a “hundred-odd women”, including the “people I met at my motivational talks”, and “that Serbian DJ, the IndiGo flight attendant, the hotel staff wherever I stayed. …”

To paraphrase a friend, who laughed in bemusement when I cited this passage, “Wouldn’t he have had better luck getting to know one woman really well instead of chatting with a hundred flight attendants?”

Indeed. And one must ask where the line lies between “feminist” “book research” and an excuse to chat up fans at his events, the staff on his flights, the employees in hotels where he stays, and, of course, “that Serbian DJ”. Because, you know, Chetan Bhagat is just that wild and crazy kind of guy who chats about feminism with Eastern Block DJs.

But Bhagat’s fake-feminist experience may have given him better insight into Debu’s character. Because Radhika’s relationship with the first man she meets in America just isn’t meant to be. Despite his awkwardly articulated claims to feminism, Debu can’t handle the fact that Radhika earns three times his salary. He wants, he tells her, a woman who is willing to stay at home and look after the children.

But Radhika is strong.

(One Indian Girl Photo by Rupa Publications)

Just kidding, this is Chetan Bhagat, not a real feminist book. Unable to handle her existence in New York without Debu, she submits her resignation at Goldman Sachs. But fortunately for Radhika, there is a man to save her from herself. Because she is a valued Associate in the firm’s most competitive unit, her boss arranges to have her transferred to Hong Kong.

In Hong Kong, Radhika meets Neel, the partner overseeing Goldman’s operations on the island. He’s a gorgeous and intelligent baniya – Radhika only seems to meet desi boys – with a British accent, a wife, and two kids. Neel, echoing peak Weinstein, puts Radhika on a project that results in the two of them spending the night at a romantic luxury resort in the Philippines.

Suffice it to say that Neel gives her an awkwardly written orgasm in mere minutes with the use of his tongue and the two embark on a torrid affair. But when Radhika learns that Neel thinks her professional drive means that she doesn’t want babies or a family, the infidelity comes crashing down.

But Radhika is strong.

Nope, still not that book. In an eerily familiar conversation, a male colleague arranges to have her transferred to London rather than give up her job.

Feminism FTW.

Back in Goa, Debu and Neel have both somehow learned of the wedding the day before it begins and crossed the world to attempt to woo Radhika back. Because what woman doesn’t love a man who ignores her explicit instructions not to crash her wedding?

Meanwhile, Radhika has been getting to know her groom-to-be, Brijesh Gulati. The awkward Facebook engineer has a few surprises up his sleeve; the two get arrested the night before their wedding for smoking joints at Curlie’s. Brijesh sees no reason why girls shouldn’t be able to smoke ganja if boys can, though he prefers “humanist” to “feminist.” His simple minded-babble seems to endear him to Radhika.

This sets up the most filmi scene of the book. At the hotel coffee shop, Radhika assembles all three boys to deliver the novel’s big feminist point: a woman doesn’t have to be a mother or a professional, she can be both. 1972 is still smarting from Bhagat’s theft of this realisation.

At this point, the reader is almost ready to give Bhagat some credit. Yes, the feminist reveal was hardly groundbreaking. But Radhika has at least told off her two stalkerish suitors – and called off the arranged marriage that she never wanted – to embark on a trip around the world.

But, after six months of world travel, Radhika stops in San Francisco. She meets Brijesh for a coffee. And although their future is ambiguous in the novel’s closing pages, the reader is left with the distinct impression that the two of them are about to begin a life together, but this time on their own terms.

It seems Radhika gets a choice between the only two assholes with whom she’s ever slept and the husband her parents chose for her. Maybe supplement your interviews with a little Nivedita Menon next time, Chetan?

(Untitled Photo of Chetan Bhagat via The Tribune)

The man gets a few points for trying. But despite all of Bhagat’s research – he claims it was exhaustive – he didn’t get very far. This shows in the white American characters who speak Indian English. It shows in the Japanese businessmen who, for comic effect, replace all of their “R”s with “L”s. I mean, think of the five Japanese words you know, I’m willing to guess that “sayonara” and “arigato” are among them. It’s the “L” sound that doesn’t exist in Japanese. Of course, once we’re quibbling over the extent of research behind the casual racism, the answer to the question may be largely irrelevant. But the worst comes when Radhika attempts to describe feminism to Brijesh. My fears were confirmed by a quick search: Bhagat had lifted parts of it straight from Wikipedia.

But despite the book’s many faults, I’ll be there when One Indian Girl is adapted for the silver screen. Mostly to find out how the producers manage to get all that cunnilingus past the censor board.

What are your views on Chetan Bhagat’s One Indian Girl? Do you think he has managed to get “feminism” correct? Share with us in the comments below.

Kerry Harwin

Kerry Harwin is a Goa and Delhi-based freelance journalist who focuses on marginal communities and the post-colonial experience. You can regularly find his work in GQ India and you can find his images and musings, along with a healthy dose of Marvin, his pink monkey friend, at @flashhardcor on Instagram.

Photo Credit: Polina Scharpova

I loved your review. You did capture the essence of the book & its shortcomings well.