Essay

Jhumpa Lahiri And Her Love Affair With Italian

Deepika Asthana

April 13, 2018

Language works as fuel for our minds as well as for our souls. It holds our memories, it helps us communicate, it comforts us with its familiarity and, over time, becomes a part of us. An invisible layer without which we cannot function, always trailing us like a shadow.

A foreign language, on the other hand, can be both- alienating as well as endearing. For example, in Italian, everything sounds romantic and theatrical. In every word, there is a promise of mystery, of covert meetings in Venetian alleys, of romantic dalliances in Florentine lanes, of family warmth.

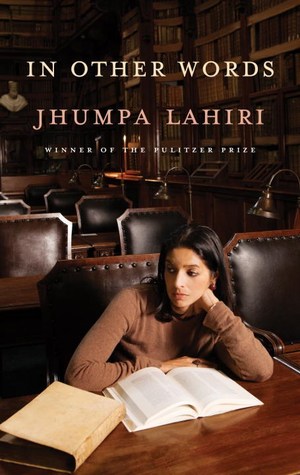

Jhumpa Lahiri has gone one step ahead and turned her love affair with Italian into a book. Her latest book, a short series of reflections on her passion for Italian, discards ‘inglese’ in favour of ‘italiano’. Originally published in Milan in 2015 as In Altre Parole, it was published in the United States in 2016 in a dual-language edition titled In Other Words.

In the short essays in the book, you get a glimpse of her love for and her struggles with Italian. She writes: “What I hear, in the shops, in the restaurants, arouses an instantaneous, intense, paradoxical reaction. It’s as if Italian were already inside me and, at the same time, completely external. It doesn’t seem like a foreign language, although I know it is. It seems strangely familiar. I recognize something, in spite of the fact that I understand nothing.”

She is as smitten with Italian as the Russian émigré Andreï Makine is with French in his rhapsodic novel Dreams of My Russian Summers. It is quite ironic that the Russian born author who sought asylum in France had to pretend that his work was a translation from Russian manuscripts in order to have his first book published. French publishers refused to believe that a recently arrived émigré could write so well in their language. The Russian Jewish author, Mary Antin was similarly infatuated with English. She wrote her classic immigration memoir The Promised Land in English, erasing the tongue of her Russian Jewish childhood. Mary Antin extols English, “this beautiful language in which I think,” and insists that “in any other language happiness is not so sweet, logic is not so clear.”

My personal flirtation with Italian began way back in the 1980s with the super hit song from the Bollywood movie “The Great Gambler”. A sweet “la, laa, laa… amore mio, dove sei tu? ti sto cercando, tesoro mio!” and it had me enthralled. The roll of the “r”, the angst in “ti sto cercando” and the lilt in “mio” all had a profound effect on me, as I am sure it did on million others. Of course, a gilded gondola bobbing gently in the canals of Venice only added to the allure of the song. This was a time when a foreign holiday meant a trip to Nepal and vacations were largely spent visiting grandparents in the hinterland (honestly, Lucknow seemed like hinterland to my 6-year old self). It was also a time when Facebook did not chronicle our existence and family holidays were just meant for the family. Yes, there was such a time, although you might need to jog your memory a bit to get there. But, I digress.

As with many childhood fascinations, my infatuation with Italian met with a quick demise. Decades later came, Eat, Pray, Love, written in 2006 by Elizabeth Gilbert and later brought to life in 2010 by Julia Roberts in a movie of the same name. Julia Robert’s attempts at learning Italian, replete with full-bodied “rssss” and emphatic gesticulations brought back familiar stirrings.

When I first read In Other Words, I wondered what could have motivated an accomplished and acclaimed author like Lahiri to abandon English for a foreign language- as beautiful as that language may be. Authors of all shapes and sizes might agree with George Orwell’s assessment that writing a book can be “a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness.” Then why exacerbate the struggle with the additional burden of a foreign language’s unfamiliar vocabulary and grammar?

Joseph Conrad, the author of Heart Of Darkness, a Polish native who began studying English only after settling in England in his twenties, is considered to be one of the greatest novelists to write in the English language. He likened his literary translingualism to arduous and dangerous labour: “I had to work like a coal-miner in his pit, quarrying all of my English sentences out of a black night.”

Immigration is a common and compelling motive for adopting new languages. However, the case of Jhumpa Lahiri is different. Lahiri wrote, “When you’re in love, you want to live forever. You want the emotion; the excitement you feel to last. Reading in Italian arouses a similar longing in me. I don’t want to die, because my death would mean the end of my discovery of the language. Because every day there will be a new word to learn. Thus true love can represent eternity.”

Maybe, In Other Words, is an attempt to create an identity for herself, which is different from that of a Bengali immigrant who excelled in English. A need to reconcile with the fact that even after moving to America, her mother resisted learning English and desperately clung to her Bengali language and culture. Estranged from both Bengali and English, Lahiri fumbles her way to Italian. “Without a homeland and without a true mother tongue,” she presents herself as perpetually being stuck in no-man’s land.

Alternately, perhaps she took refuge in a foreign language to escape from the trappings of being a literary celebrity- to work in anonymity. Echoing Beckett’s famous explanation for his turn to French (“parce qu’en français c’est plus facile d’écrire sans style”— because in French it’s easier to write without style), Lahiri affirms, “In italiano scrivo senza stile, in modo primitivo”— “In Italian I write without style, in a primitive way.” Distancing herself from the expectations created by her English style, she seems to have found freedom in Italian. In English, Lahiri is burdened with the expectations that come from being a renowned literary figure. But in Italian, she can revel in her solitude: “Scrivo per sentirmi sola”— “I write to feel alone.”

Lahiri describes her book as “una sorta di autobiografia linguistica, un autoritratto” (“a sort of linguistic autobiography, a self-portrait”). Her choice of Italian— “a language that has nothing to do with my life”—appears strange. Early on, she admits, “I don’t have a real need to know this language. I don’t live in Italy, I don’t have Italian friends. I have only the desire.” Noting how the three most celebrated translingual authors—Samuel Beckett, Joseph Conrad, and Vladimir Nabokov—all had closer and longer ties to their adopted languages than she has to hers, Lahiri writes, in Italian: “Mi chiedo se ci siano altri come me”— “I wonder if there are others like me.”

At the end of the book, Jhumpa Lahiri is poised to leave Rome and return, reluctantly, to America and English. Cognisant of her estrangement from English, a language in which she has ceased even to read, she yearns to remain in Italy and Italian. She confronts her ambiguous future with two questions: “Will I abandon English definitively for Italian? Or, once I’m back in America, will I return to English?”

While the book itself is good, although incomparable to her English language publications, her attempt to write in Italian is nothing short of commendable. Having the ability to communicate in a foreign language and a palate to appreciate foreign food is a gift. A person who has this gift can lead multiple lives, and experience myriad cultures, in just one lifetime.

Which foreign language would you learn? Which foreign language do you consider most romantic?

Deepika Asthana

Writer, investor, crypto enthusiast, nomad, mother of twins and founder of ARNA Write Strategy (a content writing agency). Deepika is a heady mix of all of that and more.

Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!