Essay

How Reading Marcel Proust’s ‘In Search Of Lost Time’ Helped Me Regain My Childhood

There are points in our increasingly busy lives when we are blessed with pockets of stillness. It could happen over a cup of tea during a break at work, or on a weekend when we’ve surprisingly caught up with all our chores. It is usually during these moments that we wonder – Where did all this time fly away? This is truly a bittersweet moment wherein we feel a warm glow, due to the beauty around us, and sadness, due to the relentless march of time.

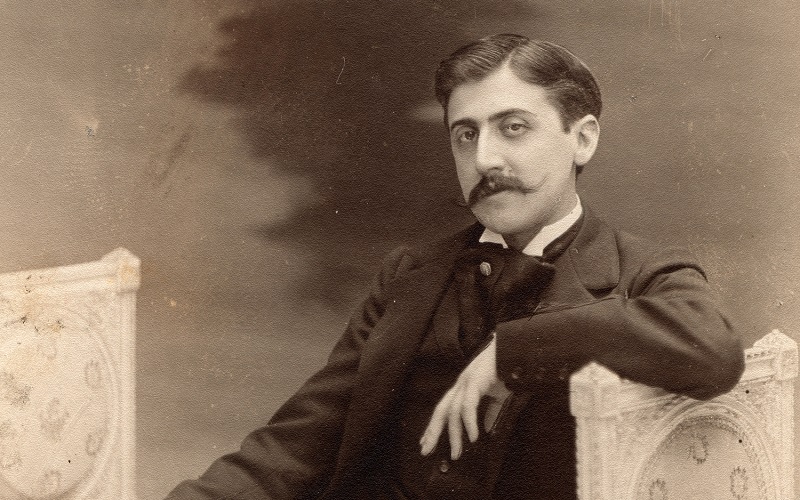

Most of us shrug off this moment and carry on with the next task of our day. But it was over a century ago that Marcel Proust, a wiry and dapper French socialite-turned-novelist, experienced a strong and involuntary recollection of a childhood memory that compelled him to go on a quest across his subconscious mind. He combed through his memories for over a decade to marry them with his vivid imagination, finally presenting his findings on life in his masterpiece À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu or In Search Of Lost Time.

The Meaningful Experiences Of Our Childhood

At the beginning of Swann’s Way, the first volume of In Search Of Lost Time, the narrator, largely based on Marcel Proust himself, sits down with a cup of tea. As he takes the first bite of a madeleine, he feels a surge of vitality that shakes him to the core of his being and, for an instant, it dissolves the weariness that comes from shouldering the many obligations and demands of adulthood. This moment, famously called the Proustian moment, reminds him of the vacations of his childhood with his well-to-do family at his great-aunt’s home in Combray, a fictional town located a train ride away from his native Paris.

On the surface, very little happens during these trips. The narrator takes long walks, observes the people of the town and daydreams. One passage describes how he is transfixed by the beauty of the setting sun as it slices across the sharp geometry of the town’s cathedral. In another passage, he recounts how he cried out in joy and wonder when he saw the clouds and the landscape reflected in a perfectly still puddle of water during a walk with his father and grandfather.

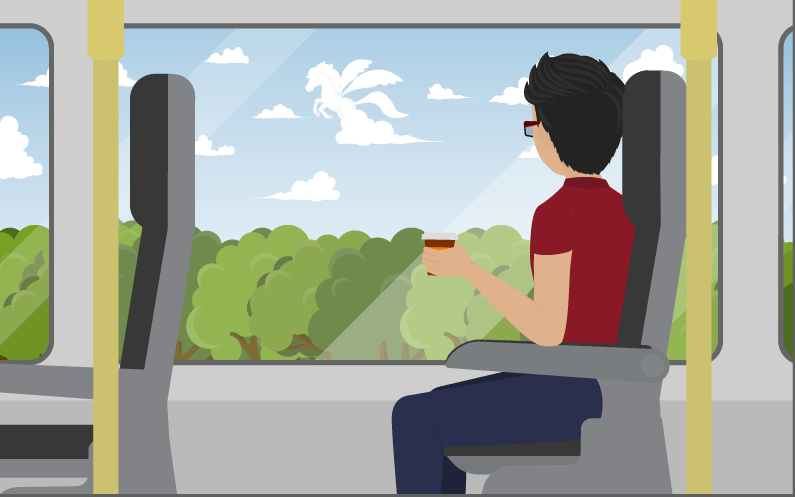

Reading these passages in my living room was a visceral experience as I was swept away by the memories of my childhood. I remember looking at the vast, puffy clouds tinged with the cotton candy glow of the setting sun and seeing a winged horse throwing back its resplendent mane like Pegasus on a bus ride from Bangalore to Mysore. And, as the bus chugged ahead, the joy and wonder I experienced multiplied when I saw the same cloud slowly morph into a moustachioed Bhagat Singh with his hat, trench coat and revolver walking ahead with a confident stride.

Over the next 500 pages, the line between my experiences and those of Proust’s narrator began to fade as the latter’s awe of the quiet grandeur of the pitched roofs and white walls of nearby towns transported me to the terrace of my aunt’s house in Karjat. I would stand on the terrace of her bungalow and take in the majestic beauty of the nearby hills, and contrast them with the humble proportions of the brick houses dotting the fields nearby.

The Pain Of Growing Up

We tend to forget that childhood is not only fun and games. The narrator’s highly sensitive temperament makes him anxious in unpleasant situations. A memorable scene in Swann’s Way is the end of the narrator’s nightly ritual — a goodnight kiss from his mother before bedtime. One night, his father forbids his mother from ever going up to the narrator’s room as he feels the narrator is old enough to not be dependent on such childish habits. Fraught with agony over this separation, the narrator endures sleepless nights and laments the cruel, often random, dependence of his fate on his father’s judgements.

I was reminded of similar nights when my hyperactive imagination conjured up spirits and monsters from the shadows on the walls, and apes that swung from their branches on the ceiling — all looking to get me the moment I fell asleep. These images frightened me till my adolescence, but my mother’s reassuring way of patting my head till I slept peacefully had, by then, been strictly restricted to the times I fell sick.

We start experiencing romantic love as we grow older. In Within A Budding Grove, the second volume of the novel, the narrator recounts his innocent, but intense affection for a red-headed girl, Gilberte, and how her various features and mannerisms left him smitten.

But what is more memorable is the surgical precision with which he describes his gradual disenchantment with Gilberte as she refuses to meet or play with him. The way in which he describes his suffering as he tries to discover the reason for being jilted made me feel as though he was talking about my first experience of romance. The narrator then resolves to delay meeting Gilberte indefinitely, reminding me of how I had avoided the girl who’d first hurt me.

While I can laugh off the experience today, Marcel Proust reminded me how formative this experience was to my outlook towards life, how it tested my limits towards pain and suffering, brought out my resilience, and forced me to get back up on my feet after a major setback. As Proust writes, ‘Those whose suffering is due to love, as we say of certain invalids, their own physicians.’

(Image via The Paris Review)

Regaining Lost Time

Like many others who are fascinated by storytelling and the written word, I toyed with the idea of becoming a writer someday. As I was introduced to the works of writers like Fyodor Dostoevsky, Joseph Conrad, Ernest Hemingway and V.S. Naipaul, I believed that grandiose adventures, exotic places and interesting, influential people were the only things needed for a great story, and that if something worthwhile needed to be said, it could only be done in a setting beyond the ordinary.

While reading the works of these great writers moved and inspired me, I also felt insecure about my life experiences — which I understood were the raw material for fiction — as they seemed to pale in comparison to what the great writers must have experienced.

This insecurity then festered into shame and resentment, and I falsely blamed my highly sensitive nature for making me so vulnerable and overwhelmed all the time so as to not experience anything ‘extraordinary’. Therefore, I chalked up the experiences of my past, including my childhood, as insignificant, and my writing ambitions as far-fetched.

But reading Marcel Proust changed all of that. He once wrote, ‘The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.’ Through his sentences of unparalleled vividness and lucidity, Proust gifted me new eyes with which I was able to re-examine the experiences of my life and, in particular, my childhood.

I realised that Proust did not view his, or anyone else’s, life as trivial, like I once did. With an all-encompassing vision, Proust patiently brought out the beauty in all things big and small. He would describe, with unparalleled finesse, how a row of hawthorn flowers blooming on his neighbour’s compound wall was as majestic as the grandeur of a noblewoman walking on the street dressed in her finery, and I would remember how I would be similarly captivated by the milky texture of the purple Vinca flowers in my colony, and the beauty of the women dressed in silk saris, sporting ornate, pearl-lined nose rings, for the various poojas and festivals.

By reading Proust, I slowly began to appreciate my experiences as moments that revealed what was most important to my being: beauty, truth and meaning. And, in this process of piggybacking on Proust’s quest, I shrugged off the labels I put on my childhood, found my faith renewed in my writing ambitions, and made myself whole again.

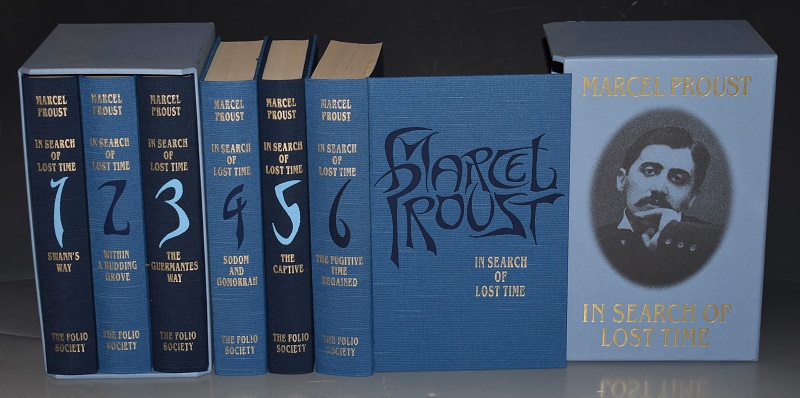

(Image via The Antique Map and Bookshop)

When Proust describes the redeeming characteristics of unpleasant people and the hypocritical ways of the seemingly virtuous, I feel these truths unfold as organically as a conversation with a good friend. I often imagine that in an ideal world, Proust and I would have met, and he would have been like the friend I never had. We would have discussed books, the sublime way a ray of sunlight in a dark room lights up the happy dance of dust particles, and the farcical ways in which adults carry on with their lives.

But, even in this less-than-ideal world, Proust has still managed to make his presence felt, in the same way as any other person would, with In Search Of Lost Time — a novel whose 1.2 million words I want to finish, but also, paradoxically, never want it to end.

Proust’s father was a doctor who headed a team that was widely responsible for wiping out cholera in France. At one point, Proust confided to his housekeeper Celeste, ‘If only I could do humanity as much good with my book as my father did with his work.’

He can rest assured knowing that he has helped many regain their lost time, and in the case of this particular reader, his childhood.

Siddhesh Raut

Books and stories have always been an integral part of my life. I explored the lives of great inventors, leaders, and mythical heroes by poring over GK books and fables and illustrated tales. But it was the Harry Potter series and Roald Dahl’s works that turned me into a proud reader. I value kindness and generosity the most in people, and the novels that bring these out resonate the most with me. When I am not working or reading, I patiently channel my curiosity into the world of jazz music, cinema, cooking, or my inner world through my solitude.

Read his articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!