Essay

An Open Letter From Nemat Sadat: Why I Call India Home

As early as seven, I knew deep within me that I was born to create an inspiring legacy. I can’t pinpoint whether it was neglect or nurture or a combination of the two that made me feel this way. This premonition for achieving greatness in my lifetime could have also been born out of my desire to prove to myself, relatives, and the rest of society that my life mattered. And, that I was worthy of love. This drive for success is quite common among LGBTQIA+ people throughout history who have heroically triumphed despite all the odds stacked against them.

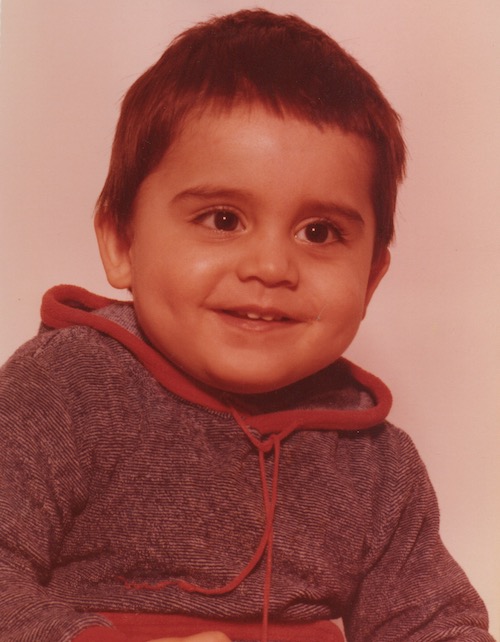

This is my story, too. I was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1979, the year that the Soviets invaded my homeland. At age five, my mother, refusing to raise her children in an Afghanistan of civil war and communist occupation, kidnapped me and my two siblings and took us to the United States. I was raised in a low-income, single parent household in Greater Los Angeles while my father remained in Afghanistan. He would later rejoin us in the 1990s.

It is against this tumultuous history of the Cold War and the turmoil that it beset on my family that I came of age, trapped in limbo—in a no man’s land—and always feeling inadequate and isolated. Even as an adult, I struggled with assimilating into mainstream Judeo-Christian America, and among the diaspora, I also felt alienated by the parochialism of Islam and burdened by the stifling rituals of Afghaniyat. No matter where I was, I was a stranger in a strange land.

My overarching identity conflict has been a central theme of my life especially in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Having my adopted land go to war with my homeland resulted in perplexing challenges as my ethnicity, national origin, and religion came under intense scrutiny and I had to continuously prove that I was apologetic, loyal, and non-violent. It didn’t help that I was a repressed homosexual as well.

It was during the first decade of the first millennium that I answered the call to adventure and experienced my intellectual awakening. My sense of conviction comes from the realisation that the meta structure of the universe was rigged against the aspirations of an ambitious gay Afghan refugee from Duranni Pashtun and Sunni Muslim tradition to live a fulfilling life. Trying to assimilate into American culture didn’t give me the inner peace I was seeking when I realised that I was being whitewashed into letting go of a rich cultural heritage that traces back 2500 years. My struggle is best expressed when Kanishka Nurzada in The Carpet Weaver says: “An eerie feeling beset me as the thought of being true to myself felt beyond the realm of any possibility. I felt like a thousand shattered fragments of the true mirror I yearned to be.

In 2012, I returned to my birthplace, Kabul, after living three decades in exile, to work as a professor of political science at the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF). While I tried to remain discreet, I was still persecuted for being a practicing homosexual and lapsed Muslim. Instead of caving into the demands of orthodox Muslims, I fought back by meeting gay men in the Afghan capital and clandestinely mobilising an underground movement and using social media to openly campaign for LGBTQIA+ rights.

A year later, I was forced to resign from my post and threatened by the Afghan government that I would be arrested, taken to court, and handed down either a life sentence or the death penalty, even though I was a naturalised U.S. citizen. The Afghan government alleged that my physical presence and self-expression was destabilising the social order of Islam.

At the end of the academic year, I went to New York City and in July 2013, the Afghan government alleged that my public outreach was subverting Islam in Afghanistan, so they pressured AUAF to fire me. A month later, from my new bedroom in the Upper West Side, I took a huge leap of faith to announce my sexuality on Facebook in a plea to reconcile my identity conflict and finally be accepted by my family and nation. I ended the war that was raging in my head by concealing my secret for the last 34 years of my life. But even some of my non-Afghan and non-Muslim American friends distanced from me on the grounds that I had become too controversial. And of course, I received numerous threats and curses from Muslim purists.

In my most trying days, I was jobless and broke and when I couldn’t pay my rent on time, I found myself languishing in a homeless shelter in Brooklyn surrounded by the living dead. It was during this experience of obscurity that I formed the sentiments expressed by Kanishka Nurzada in the internment camp scene when he says, “But it was here that I learned that you cannot shatter the broken, control the nonconformist, or scare the fearless, for they have nothing to lose in proving their willpower and worth.”

My stubbornness annoys the people closest to me. But it’s also the reason why I’m victorious in getting The Carpet Weaver published today. I could have quit after I received 450 agent rejections in the US and the UK. But I refuse to fall victim to the “woe is me” narrative that is used to pigeonhole gay people. I continued to champion The Carpet Weaver until I made a breakthrough when I submitted a query letter to India’s top literary agent, Kanishka Gupta. Within days, he had read my manuscript and responded with an offer to represent me. The rest is history.

I started writing this open letter during my transatlantic journey to Mumbai and a million thoughts rushed through my mind as I imagined the thrill of celebrating The Carpet Weaver’s early success and launching my debut novel on the first anniversary of India’s legalisation of same-sex relations. Where else would I be on this historic day? Outlawed in my homeland for being a kuni and speaking blasphemy and unpublished in my adopted land for writing a post-conventional novel, it was an instinctive for me to travel to the India—the only country so far where I can express myself as both an activist and an author and be venerated for the words that I speak and write.

In June, when I traveled to India for the first time, I released The Carpet Weaver at the Imperial Hotel in Delhi—the site where Mahatma Gandhi, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Lord Mountbatten met to discuss the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent. I come with a different message. One that speaks of unity and unification. I see India’s place in the world as a spreader of love—a love that is now inclusive of all people. Given India’s rich cultural footprint, I truly feel India is the gateway to broader discussions about LGBTQIA+ literature in the rest of Asia and in the Muslim world. This puts India’s emerging LGBTQIA+ community in a unique position to expand its sphere of influence by harnessing the potential of the literary arts. For there is no greater force in changing the world than the power of good storytelling that breaks boundaries and challenges preconceptions and prejudices.

The question is how do you create a space for opening up conversation about homosexuality in countries that are still hostile to narrators like Kanishka Nurzada and other lead characters who transgress society’s rules and upturn the status quo. By allowing the voices of queer campaigners fighting for equal rights to be heard and letting subversive literature like mine be published, India has demonstrated that it is honouring its commitment to democratic principles and ideals. I am comfortable in my own skin and feel whole in the land of love.

This is why I call India “home”, and I’m forever grateful to my Indian readers and everyone else who has treated me like a crown jewel.

Read an excerpt from The Carpet Weaver here.

Nemat Sadat

Nemat Sadat is a prominent activist and journalist currently based in Washington, D.C. He is the first native from Afghanistan to have publicly come out as gay and campaign for LGBTQIA+ rights in Muslim communities worldwide. While teaching at the American University of Afghanistan, he secretly mobilized a gay movement off campus but was then persecuted by the Afghan authorities and deemed a national security threat for allegedly subverting Islam. Sadat has previously worked at ABC News’s Nightline, CNN’s Fareed Zakaria GPS and the UN Chronicle, and has earned six university degrees, including graduate degrees from Harvard, Columbia, and Oxford. The Carpet Weaver is his first novel. He can be found on Facebook: @MisterNemat; Twitter: @nematsadat; Instagram: @nematsadat

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!