Excerpt

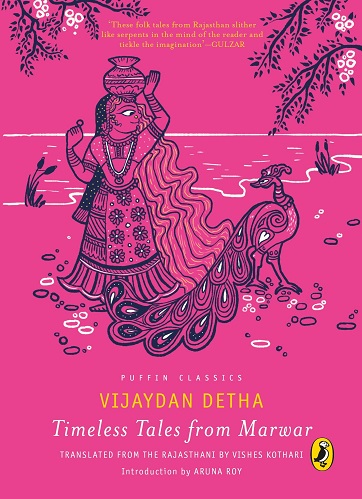

Timeless Tales From Marwar

The Learning Of Toil

‘In old handwritten manuscripts, there is a story of about a page and a half. Which I extended . . . added many a twist to the conversation between Raja Bhoj, the old woman and the Pandit . . . one of the foremost tales in the world. How else could I pay off the debts I owe to my gurus?’

—Bijji

It was the reign of Raja Bhoj in Ujjain Nagari. Widely loved, ocean of knowledge, fount of wisdom, patron of the arts. Merciful, righteous, protector of the realm! The people of the kingdom respected him like their father. Anyone could approach him without fear and talk to him; the raja would meet them as equals. He would roam the kingdom alone and find out about the people’s pain, erase their suffering and fulfil their wishes. At his court, poets, intellectuals, singers and men of letters were greatly respected. The court of Raja Bhoj in Ujjain Nagari was the centre of an unparalleled gathering of intellectuals. Even the birds and animals were wise and learned. Every day, the durbar was held and there were debates and discussions. The glow of the raja’s name spread to every home.

One day, the raja asked his pandits and intellectuals, ‘Where can one find the Garden of Knowledge?’

All the poets and intellectuals who fed off the grains of the court, replied that of course it was none other than the court itself! The foremost place of knowledge was the Raj Durbar, followed by the fortresses and castles, and then the havelis and mansions. ‘Where there is power and wealth, there follow knowledge and artistry. And without wisdom and learning, wealth and power cannot be amassed,’ they replied. ‘And so, the luckless poor lack wisdom and knowledge and hence lack wealth and power.’ All the intellectuals said the same thing in different-different ways, giving different-different examples. Intellectuals of such stature were all saying it with so much conviction that Raja Bhoj had to believe them!

A gardener was listening to these discussions quietly. Finally, he said, ‘Annadata1 . . . !’

Raja Bhoj cut him off. ‘Again the same thing! I have explained to you people a thousand times that I am not the Annadata, you are! I am just a shepherd.’

The gardener accepted his mistake and said that it would take time to change this habit of generations. Then he said, ‘I have become tired merely listening to these discussions about this Garden of Knowledge. Neither have my ears heard of such a thing nor have my eyes seen it. So, it is pointless to argue about it. If you want to see a garden of the miracles of nature, come with me to my garden. I came to the Durbar to invite you.’

Accompanied by the Magh Pandit from his court, Raja Bhoj left instantly. The garden was five miles out of the city. The three of them reached the garden at midday. So many colours! So many scents! In the lap of that green earth danced many vibrant flowers. To see nature in such bounteous bloom was to make the gift of light to one’s eyes meaningful! The raja got lost as his sight danced among the flowers in that garden. The Pandit kept reminding the raja of the time, so they finally started to head back. The gardener offered to accompany them on the way back, lest they lose their way, but the raja wouldn’t hear of it.

After about a mile and a half, the King and his priest lost their way. Surely they had not crossed these fields of wheat on their way to the garden earlier! Helpless, they looked around. At the edge of the field, they saw a dokri standing. White hair. Completely bent. Trembling head. Guarding her fields from birds. They went near her and folded their hands in greeting. ‘Live long, sons,’ she said.

The raja asked her, ‘Ma, where does this road go?’ She smiled before she answered. Her toothless smile lit up her face like starlight. Then she raised her head to look at the raja and said, ‘Beta, this road will stay where it is. But the travellers who walk on it come and go.’

Then she asked them, ‘Beta, who are you?’

‘We are travellers of the road.’ She said, ‘Ni, beta. The travellers of the road are two others!’

This time, it was the Pandit who asked, ‘And who are they?’

‘One, the sun, and the other, the moon. They move across the sky, night and day. Don’t stop for a second. They are the travellers. But tell me, who are you?’

They said, ‘We are guests.’

She said, ‘Ni, beta. The guests are two others. They are youth and wealth. They never stop for long. They are guests. But who are you?’

‘We are pardesis.’

‘Ni, beta. The pardesis are two others. They are the wind and the jeev. The jeev leaves and no one sees it go. And it is because of the wind that this body sustains. And no one can stop it from leaving. Both are invisible. No one sees them go, and once gone, they never return. They are called the pardesis. But beta, who are you?’

They said, ‘We are poor men.’

‘Ni, beta. The poor are two others. They are the calf of the cow and the unmarried daughter. The bull ploughs the soil of who it is sold to, and the daughter lives for who her parents marry her to. The poor are those who must live according to the whims of others. But beta, tell me, who are you?’

The raja was really enjoying listening to the dokri. Wanting to test her wisdom, he said, ‘Ma, we are thugs.’

She shook her head. ‘Ni, beta. The thugs are two others. They are the king and the moneylender. The farmer toils and labours, while the king measures and gobbles. The moneylender fudges his accounts and charges twenty-one instead of one. Who in this world can be a bigger thug than these two? They thug everyone and yet pass off as great men. But tell me the truth, who are you?’

‘We are the inebriated.’

‘Ni, beta. The inebriated are two others. One is the devotee and the other, the scholar. The intoxication of drink wears off with time. That is no true intoxication. The devotee is intoxicated by his faith, the scholar with knowledge. What sort of rubbish drunks are you!’

They said, ‘We are liars!’

She said, ‘Ni, beta. The liars are two others . . . They are the sadhu and the atheist. The sadhu says he knows God, and the atheist says there is no God. I think there are no bigger liars than these two. But you know neither truth nor falsehood. All you know is to play games with me, which you are still going on with. Ram-damned, at least now tell me, who are you?’

‘We are tricksters.’

‘Ni, beta. The tricksters are two others . . . They are beauty and the ego. However proud of them you might be, they trick you and leave you in old age. Toothless mouth, white hair, bent back, sagging breasts—is this any small trickery? In one’s youth, one thinks one can pierce the skies, but in old age, one cannot even shoo away the flies on one’s face. Seeing me, don’t you see what these two tricksters have done to me? But tell me, who are you? It’s almost evening and you still can’t answer a simple question. Who are you?’

This dokri was challenging everything they said! Today, both the men had forgotten the way back home, but they had also forgotten the path of learning and wisdom. The woman had entangled them in such a web that they could see no way out. Their pride and arrogance of years were shattered in seconds! Where the intellectuals of the Court were saying the Garden of Knowledge was, and where it had turned out to be!

Raja Bhoj finally said, ‘We are losers.’

The dokri still would not give up. With that same smugness, she said, ‘Na, the losers are two others. One is the indebted, and the other is the tiller of the land. A man can bear the weight of a mountain on his head, but he collapses under the weight of debt. And the tiller moves his hands and legs as per the wishes of others for the sake of his stomach—who can be a bigger loser than him! Beta, in this world, these are the two losers. But who are you, tell me? I’m losing my patience now, but you’re still not telling me the truth.’

After listening to the dokri’s words, the raja felt no anger. Nor was the Pandit willing to give up. Who could be more tolerant than these two! Raja Bhoj said, ‘We are the tolerant.’

The dokri had not been born on such a night as to let this pass without challenge. She said, ‘Na, who would call you tolerant! The tolerant are two others. They are the earth and the tree. The earth bears the weight of sinners and those without karma. We tear her chest apart and sow our seeds, but she still won’t destroy the seeds. We plough her chest, but she still fills our stores with grain. We dig deep pits into her heart, yet she gives us sweet water and hands us priceless wealth, such as diamonds, pearls and gold. We cast stones at a fruiting tree, but it still gives us sweet fruit. When cut, the trees give us light and cook our meals. Even when burnt, they provide. They are named tolerant. In the middle of all this talk with you, I forgot to guard my fields. The naughty birds are having a great time!’ she said, as she let off a shot from her sling and came and stood by them again.

The raja still felt no anger at the dokri. Who else but a saint could bear so much! Thinking this, the raja said, ‘Ma, we are sanyasis—the renouncers.’

‘Na, the renouncers are two others. One is he who is satisfied, and the other, who does not know. The man who has no greed at all in this world—not of wealth, nor fame, nor God nor knowledge—it is he who is a renouncer. Either he who knows everything can be so satisfied, or he who knows nothing! These are the only two people in this world who can be called renouncers. Now, it is about to be evening and you are unable to answer such a small question. What fools are you?’

Now it seemed best to admit defeat to the dokri. Thinking this, the Pandit finally gave up and said, ‘We are fools of the highest order.’

‘After eating my head for so long, finally you tell me the truth! Indeed, in this world there are only two fools—the raja and the Magh Pandit. The most ordinary raja begins to think himself equal to God! And surrounds himself with sycophants, who use their empty gyan to feed this lie.’

She then turned to look at the raja and said, ‘You are Raja Bhoj and this is the Magh Pandit. Beta, why did you feed me all this nonsense? Have I lived off the crumbs of the Raj Durbar and wasted all these years? I see with my eyes, hear with my ears and think for myself. Those who live off the crumbs of the Court do not think, hear or see for themselves. But beta, those who live off their own toil cannot afford to do so. Only those who eat for free can afford such folly.’

By now, the Pandit was annoyed with the old woman. He said, ‘This is all just clever wordplay. I will ask her a question, and we will get to know her wisdom only if she can answer.’

The old woman started laughing and said, ‘Whatever for? Whom must I prove my wisdom to? Those who must prove their learning to others have some selfish need to do so. I am content as I am. Even then, ask if you must. If I know, I will tell you. If I don’t, I won’t hesitate to say I don’t know. This poor human being—how much can one know of this endless universe? Only the illusion of knowing . . . ’

—

due credits/copyright to the book title, author (Vijaydan Detha), translator (Vishes Kothari) and the publisher.

Text copyright © The legal heirs of Vijaydan Detha 2020

Translation copyright © Vishes Kothari 2020

Popularly known as Bijji, Rajasthani writer Vijaydan Detha is one of the most prolific and celebrated voices in India. He has been conferred with the Padma Shri, Rajasthan Ratna Award and the Sahitya Akademi Award, among various others, for his writings that span decades. A financial consultant by profession, Vishes Kothari is a native of Sadulpur in Rajasthan and has a keen interest in the oral and musical traditions of his state.

Excerpted with permission from Timeless Tales From Marwar, Vijaydan Detha, Vishes Kothari (Tr.), Puffin, available online and at your nearest bookstore.

Entertaining excerpt. Scathing satire disguised as good-natured wit. The ‘lesson’ at the end is simple, but brutally true. Our station in life, and whom we depend on — fundamentally shape our worldviews.