Feature

Barbed Wire Fence: How The Partition Impacted The Lives Of Women In The Barak Valley Of Assam

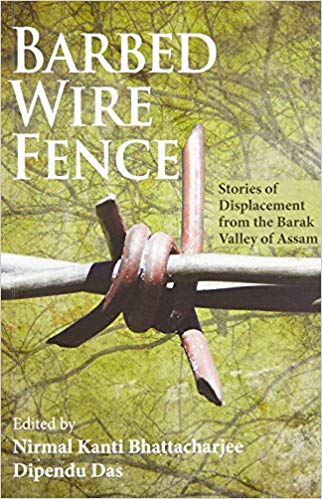

Not many have heard about the collection of narrative experiences in Barbed Wire Fence: Stories Of Displacement From The Barak Valley Of Assam. In Partition studies, there is an imbalance in the study of the experiences of women from the northeast, who experienced Partition very differently from those of Punjab and the West of the country. For them, the process of Partition was not a one-time incident that took place, but an ongoing process with a long history, that started with the seeds of hatred sown during the first partition of the province of Bengal in 1905.

The Barak Valley of Assam is a unique case in Partition historiography. A major displacement of people took place here after the referendum in Sylhet district on July 6 and 7, 1947, when Sylhet voted to join East Bengal, and other than a small Hindu majority pocket, most of the district was transferred to Pakistan. However, there was still a free flow of population in the area till 1948, and in 1971, there was a huge influx of refugees post the Bangladesh Liberation War. This caused an ongoing animosity from those who considered themselves Assamese towards the “outsiders”, over a fight for resources.

Thus the issues of who belongs to the state have always been a contested identity, fought over not just communal lines but also linguistic. More so, the experiences of women and their movement towards becoming citizens of the country are fraught with anxiety and have still not received closure.

The Politics Of Barbed Wire Fence

“According to Dipendu Das, the genesis of the book Barbed Wire Fence, was a national seminar on Marginal Literature several years back, where the delegates from different parts of India informed him that they were unaware of the fact that a huge number of Bengalis live in Assam and produce literature in Bengali. That sparked the idea of publishing a book representing one of the most significant issues in the lives not merely of Bengali people of Assam, but also in the post-colonial studies, he says.” The political act of creating an anthology that specifically represents the concerns of the Barak Valley of Assam breaks the relegation of this literature to the periphery.

The book is a compilation of translated works from Bengali into English, where second-generation authors deal with issues of displacement, fragmented identity and longing for a homeland. In the language battles of Assam, issues of language identity and legitimacy played out in the aftermath of the Partition. There is not much awareness about the literature of the Bengali-speaking community, a minority in Assam, as they are neither absorbed by the mainstream Bengali literature, which does not consider them as part of the tradition nor is their literature seen as Assamese as it is written in Bengali. The stories provide a counter-narrative of the nation, challenging the hegemonic understanding of the literatures of the region.

Two of the short stories in Barbed Wire Fence directly tie into the issue of women’s citizenship. Through them, you will be able to see that the experience of citizenship is not universal, but a gendered process.

Identity And Citizenship In Wake Up Call

In the story, Wake Up Call, we see the relationship of the second-generation narrator with Masi, an old widow who is unable to understand the need to provide documentation in order to return to her homeland. His narration highlights how the state-sponsored history written in textbooks is a linear constructed history. In being constituted as a citizen, one is called to subscribe to this idea of the nation and abandon allegiances to other territories. However, the memory of Masi’s homeland which does not correspond to the newly marked territories fails to fall in line with this understanding of the nation. The individual’s relationship to this history and the narration of the personal history counter the grand narratives of the state. Masi’s narration goes back and forth in time; her lived experiences do not follow the neat territorial boundaries and chronological time. The way men and women experience citizenship is not universal, but is gendered and marks the bodies of women and their identity.

Masi does not fit into the neat categories of society and thus is not considered a full member of the society. Her failure to conform leads to a constraint on her mobility. The narrator says, “For the countries on either side of the barbed wire, she is merely a nonentity.” Her relation with the state is not recognised, as she is not an economic asset but rather a liability to the state.

Masi’s relation to the land and space is not understood in terms of national cartography but rather rooted in familial ancestry. After a failed attempt to cross and return to her homeland, she starts to collect torn discarded papers with any semblance of official documents. Masi’s performance of collecting torn papers in order to prove her citizenship is referred to as a mania, an attempt to possess the marked citizenship necessary for her to go back to her homeland. For women, the right to citizenship is a negotiation of one’s identity in relation to the community, the family, one’s religion and is a complex performance fraught with risks and challenges to one’s agency.

The bureaucratic processes fail to take into account the lived experiences of women. The issues of having to formally prove one’s belonging to the land and the right to possess formal documents are also seen in the next story.

(Image via Scroll.in)

Anxieties Of Citizenship in Parbati’s Household

From the title of the story, it is evident that traditional gender roles have been reversed with Parbati being the head of the family. She is also the one who finds out their name is not on the voting list. In Parbati’s Household, the landless and seasonal nature of Parbati’s husband Dasharath’s job does not offer him the security of employment. “Dasharath’s forefathers had also spent their entire lives at the Barasingha Tea Estate but nobody had ever got a ‘permanent job’ at the estate. Neither did Dasharath. And how would Parbati even try hailing from a different tea garden altogether?”

Parbati, as a new bride, confessed her love for plucking tea leaves to Dasharath and said that she had often helped her mother pluck leaves at the Chandighat tea garden. This tea garden, which is in Assam, shows that Parbati is at least the second generation born and living in Assam. Parbati and Dasharath’s families had worked in the estates for generations; however, they have nothing to prove this. The concept of marked citizenship in having to prove one’s lineage or have valid documents to secure legitimacy comes through in Parbati’s despair. Their names do not appear on the voters’ list although they have lived on the land for generations.

Dasharath believes in a certain benevolence of the state, that it will protect them. For the subaltern citizen, state-offered legitimacy is a matter of basic survival. The citizen is dependent on the welfare state for access to resources, to rations of food; Dasharath and Parbati’s legal status also determines whether they will be employed. The state’s processes for enumerating citizens are not made accessible to the common people, who are cut off from the discourse of power and the state. The enumeration process only relies on a randomly selected cut-off date as the criteria for citizenship. It fails to take into account one’s belonging and the history of the land, which is not linearly constructed.

(Image via India Today)

The literature of the Barak Valley of Assam shows us that the Partition was not just an event in the past but a process that still shapes the lives of the people. The loosely demarcated and porous borders of the region still throw up questions of citizenship and identity, which are strongly contested.

The violence and division between the Brahmaputra and the Barak Valleys, that left scars in the minds of many, was also responsible for the animosities between the peoples of the two valleys. Barbed Wire Fence shows us that by denying their history of belonging to the land, there is a denial of their historical rights to citizenship.

Have you read Barbed Wire Fence? Do you know of any other books which highlight the issues in the Barak Valley? Tell us in the comments below.

Rhea Pereira

Rhea has completed her Masters in English at SNDT Women’s University. Her key research interests are post-colonial studies, mainly focussing on women’s narratives and their experience of citizenship. Her other interests are Dalit literature in translation. She also sings in a choir.

Rhea is the social media manager at The Curious Reader. Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!