Feature

The Bias Of The Biographer

Deepika Asthana

May 16, 2018

They usually have everything: a (nonfictional) protagonist, vivid and fairly well fleshed out support characters, a storyline in motion and more. What they also have are facts, which many readers find comforting. “Why not say what really happened?” wrote the American poet, Robert Lowell.

Biographies are intended to take the shape of the person central to the story. However, it is more often than not inflected with the author’s distinctive voice. To produce a biography that reads like a novel can be extremely challenging. It involves lots of meticulous research that can help the author reconstruct life events, evoke memories of historical and social backgrounds, create drama and give a voice to the central character. It also involves a bit of imagination. Artfully weaving it all together to create a story that has the narrative sweep of fiction, but is actually true, is the job of the biographer.

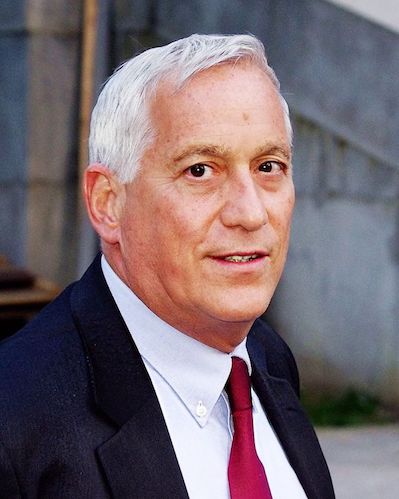

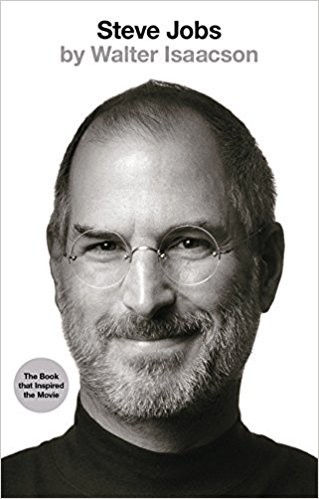

Leaving the detailing of one’s life in the hands of another requires a great deal of courage. Steve Jobs gave this honour to Walter Isaacson who received the gift of exclusive interviews with this tempestuous visionary. The biographer’s written account is, in many cases, what goes down for posterity. Often it is how the subject is remembered, for better or for worse. Thus, a great deal of responsibility falls on the biographers’ shoulder. Consequently, biographers hold an incredible amount of power, and they can choose to wield it in a number of ways. However, writers who take on the role of detailing others’ lives also tend to invite more criticism and critique. Their own life’s work may be judged based on the justice they have done to another’s life and work. Many felt that Isaacson’s portrayal of Jobs in Steve Jobs was polar and blinkered by his own inability to understand the power that Steve Jobs was. Isaacson and his book were at the receiving end of much contempt as many people accused him of focusing too much on Jobs’ flaws and boorishness and very little on his accomplishments. In an attempt to put a positive spin on Steve Jobs, a new biography titled, Becoming Steve Jobs was written by Brent Schlender and Rick Tetzeli.

What is most obvious is that every biographer has an agenda of his own. A biographer’s take on the life he spotlights is necessarily biased by his own opinions. While this can add colour to the biography, it can sometimes be a really a fine line between fact and fiction- a line that the biographer should ideally not breach.

However, as a human being, is it even possible to be completely unbiased? To keep the biography away from even a shadow of personal conflict or opinion. I think not. I believe that when the biographer gets consumed by his subjects’ life, there are times that the boundary between what the subject thinks and what the biographer believes the subject to think, gets blurred. Some of the greatest biographies ever written are said to have been afflicted by this malaise.

Walter Isaacson by David Shankbone [CC BY 3.0 ], from Wikimedia Commons

Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Brontë has been attacked by many for being a very biased portrayal of the famed author. Gaskell’s The Life of Charlotte Brontë is considered one of the most remarkable literary publications of all time. Gaskell focused on Brontë’s personal life rather than on her accomplishments. In her book, Gaskell aggressively tried to salvage Brontë’s reputation, which was viewed by many as godless. By carefully selecting anecdotes and letters and censoring less flattering aspects of her life (such as her open love for a married teacher), Gaskell shaped Brontë into a heroine of towering virtue – a paragon of morality, duty, and sacrifice. In her zeal to defend Brontë’s honour, Gaskell completely camouflaged the indomitable spirit of the woman who created the feisty Jane Eyre.

Many people disagreed and attacked Gaskell’s portrayal of Brontë. Tanya Gold in a piece for The Guardian wrote, “Elizabeth Gaskell is a literary criminal, who, in 1857, perpetrated a heinous act of grave-robbing. Gaskell took Charlotte Brontë, the author of Jane Eyre, the dirtiest, darkest, most depraved fantasy of all time, and, like an angel murdering a succubus, trod on her. In a “biography” called The Life of Charlotte Brontë, published just two years after the author’s death, Gaskell stripped Charlotte of her genius and transformed her into a sexless, death-stalked saint.”

Another biography that cemented both the biographer and the subject’s name in history was James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson. It has been heralded by many as the greatest biography written in the English language. In fact, May 16 is observed as Biographer’s Day to commemorate the anniversary of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell’s first meeting on May 16, 1763. Even though Boswell was nearly three decades Johnson’s junior, they became close friends and shared a common interest in writing, literature, and literary critique.

Boswell shadowed Johnson and spent many years of his life in constant awareness of his subject. He recorded everything, and he didn’t withhold much of anything in the biography. He painted a candid picture of Johnson, including his faults and his less-than-glamorous traits. In one case, Boswell wrote so thoroughly regarding Johnson’s stammers and outbursts that experts were able to posthumously diagnose him with Tourette syndrome. His approach to penning the biography is considered legendary. Yet, his work is not devoid of critique.

Boswell has been accused of taking too many liberties and changing quotes in order to skew the story in favour of how he perceived Johnson and more importantly how he wanted to tell Johnson’s story. Boswell chose to focus more heavily on Johnson’s later life and did not pay too much attention to his early years. While this could primarily be because it is only in the later years that his acquaintance with Johnson grew, it does not justify the apparent “omission”.

James Boswell, (Engraving by J.W. Cook from Wellcome Library, London; vignetted & converted by User:Odysseus1479 [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

In the end, the biographer chooses to tell some parts of the story and omit other parts. He also chooses the way in which the story is told. These decisions can heavily impact the “facts” of the story. However, we can all agree that writing a biography is more of a “life project” rather than a “short story”. For many biographers, it has been their magnum opus. Biographers bring the stories of people past and present to the present and store it for future generations. This gives them immeasurable power which they should choose to yield judiciously.

Do you think it is possible for a biographer to be objective while writing a biography? How does the bias of the biographer affect the way the book turns out? Share with us in the comments below.

Deepika Asthana

Writer, investor, crypto enthusiast, nomad, mother of twins and founder of ARNA Write Strategy (a content writing agency). Deepika is a heady mix of all of that and more.

Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!