Feature

How The Traditional Cookbook Evolved Into The Food Memoir

A few years ago, when I was studying abroad, I cooked my mother’s recipes with a vengeance – I would make yakhni pulao or khichdi and devour it with a sense of homesickness. I would beg fellow Indians to bring garam masala from their travels home, just so I could find some familiarity in it. Cooking late into the night also became the only way to survive my time out of home. Food and memory became so intrinsically linked that I was bemused at my own ability to find solace in the kitchen.

Now, several years into having my own home and being obsessed with baking all the time, I have realised how much comfort I derive from reading cookbooks and stories about food and cooking. Food and cooking express the untold stories of our lives, and it is reassuring to be able to read about people’s memories related to how they prepare and serve food from all over the world.

Through my essay, I will be looking at food, cooking and cuisines as depicted by traditional and modern cookbooks, and how the basic cookbook evolved into the modern food memoir. I will chart what spurred this change, and unpack how food memoirs have become a conduit for nostalgia and unearthing memories. Additionally, I will examine why readers prefer memoirs that focus on the art of food and cooking, instead of traditional cookbooks.

The Death Of The Cookbook

The memory of food is a thing of nostalgia, and cookbooks are the monuments that hold this nostalgia in place. Published in 1955, Dharam Jit Singh’s Classic Cooking From India was one of the oldest cookbooks detailing Indian cooking. It had elaborate narratives of India and its traditional dishes and became the first cookbook of its kind to be published in the U.S.A. The book primarily demystified several myths about Indian cooking, especially those related to the myth of the Indian curry. Journalist Santha Rama Rau in her New York Times review in 1956 described it as a ‘pioneer attempt’ to persuade Americans that Indian food was ‘not the gummy, pasty mess known here as curry’. A little more than a decade later, Rau wrote her own cookbook called The Cooking Of India, modelled after Singh’s structure, and packed it with the geography, customs and traditions of the country and how it influenced food and memory.

Traditional recipe books such as Rau’s and Singh’s were modelled on the lines of Elizabeth David’s French Country Cooking and Irma Rombaeur’s The Joy Of Cooking, where a set of instructions were provided to professional and amateur cooks on how to handle classical ingredients. But these cookbooks failed to provide the canvas against which these instructions would operate, and felt almost pedantic in the way they looked at various cuisines. Moreover, they also fell short in creating a culture, where the mainstream traditions of cooking would give way to include diverse voices. In fact, many of these cookbooks were unidimensional – providing no space for improvisation, no space to interact with the authors’ own experiences and no conversations with the ingredients they had chosen.

Even in the 1990s, most Indian cookbooks did not break away from this formal voice. Madhur Jaffrey’s At Home With Madhur Jaffrey: Simple, Delectable Dishes From India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, And Sri Lanka, Mridula Baljekar’s The Complete Indian Regional Cookbook and Sanjeev Kapoor’s How To Cook Indian are all cookbooks that understand the best use of South Asian flavours. But these cookbooks only provide a stepping stone towards the nuances of food – they are purely instructional, with recipes and with little to no cultural context, almost removed from the authors’ own preservation of memories.

Readers, by this time, had also discovered that they wanted to converse with the author and the recipe alike. Matt Sartwell, the manager of the New York bookstore, Kitchen Arts and Letters, speaks about bringing a personal voice within cookbooks, a narrative that would evoke something deep in the reader. Keeping this mind, a good and personal cookbook would need to be a well-structured, interesting and witty narrative that would evoke vivid scenes in the readers’ minds, and have a plot so intriguing that it would thicken as quickly as the curry does.

Traditional cookbooks lacked this vivid and delicate balance between the personal narrative and the delivery of the recipe. Readers are not necessarily looking for a story within each ingredient, but sometimes, it is best to provide elements within a recipe that would strike a chord in their minds, and make them remember something personal about their own lives. This impetus would not just help readers to remember the recipe, but would also open a dialogue between the writer and the reader.

Because the cookbook could not stretch itself like a bridge to accommodate the desires and voices of readers, it led to the rise of a completely different genre of books that honour food: the food memoir. Very distinctive from the cookbooks of yesterday, these books, in addition to recipes, give us a narrative that not only highlights the ingredients but can also be read as a personal essay on the lived experiences of the author.

Interweaving Of Food And Memory

The genre of the food memoir is widespread and its success is supported by the fact that a simple plate of food can ‘set off such a frenzy of thoughts – of people, places, time, tingling all your senses at once – taking the form of a kind of soul stirring carnival in your head’. Food memoirs are not just about the recipes. Barbara Frey Waxman, in ‘Food Memoirs: What They Are, Why They Are Popular, And Why They Belong In The Literature Classroom’, tells us how food memoirs are ‘about the treasury of metaphorical associations that link food with love and emotional nourishment that are often present in the personal histories and confessions of food memoirists’ and about ‘associations of food with cultural identity, ethnic community, family, and cross-cultural experiences’.

Though the term ‘food memoir’ has only recently been subsumed by the lexicon of food writing, the genre is said to have begun in 1825, with the publication of French writer and gourmand, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin’s The Physiology Of Taste: Or Meditations On Transcendent Gastronomy, where he took readers through a journey on the close links between smell and taste. He believed that understanding food would help people understand the world, famously saying, ‘Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are’.

Food memoirs are significant because firstly, writing and reading about food within a larger narrative can help process lived experiences; secondly, they legitimise quotidian experiences of preparing, serving and eating; and lastly, they challenge mainstream cultural scripts, in which alternative and vulnerable identities may not be accepted.

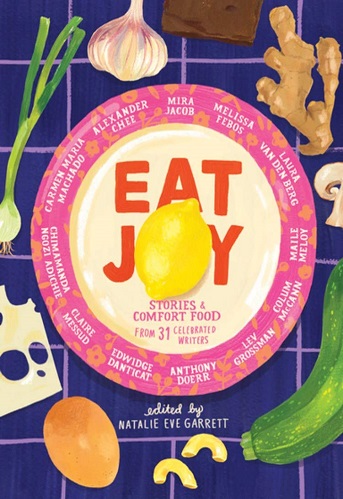

Natalie Eve Garrett’s Eat Joy is an illustrated anthology of essays by 31 different authors about the magic of comfort foods – and their recipes – and how cooking these have helped them survive challenging times in their lives. The collection does something unthinkable – it gives you a taste of love, loss and grief, while also reminding you that food and cooking are restorative. Eat Joy does the work of seeing the author as well as the reader, thereby, creating a beautiful relationship between the writers, the food they discuss, as well as the readers’ own experiences.

(Image via Saveur)

Maira Kalman’s Cake, on the other hand, seems almost like a reverie – it is a cookbook for cakes, punctuated by Kalman’s Matisse-like paintings and stories from her childhood. The book is a collection of her memories – both happy occasions as well as sad – and the recipes are timeless, connecting the concepts of food and memory together.

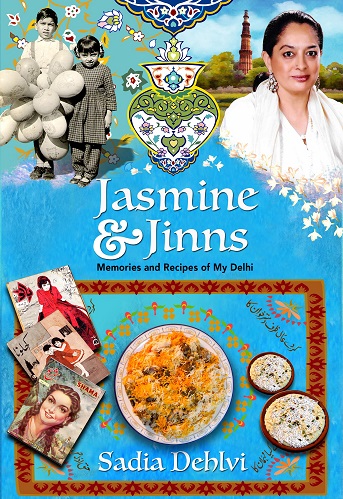

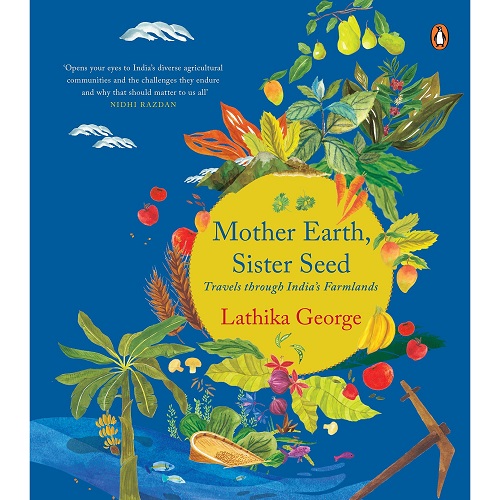

Sadia Dehlvi’s Jasmine And Jinns and Lathika George’s Mother Earth, Sister Seed provide an experience of understanding the mundane processes of preparing, serving and eating food. Dehlvi’s book is a poignant journey into Old Delhi, as she weaves stories of her childhood with the beauty of Delhi’s ancient past and cuisines. It is her endeavour to become one with the city through food. Mother Earth, Sister Seed, on the other hand, is a rare food memoir that speaks of ‘our umbilical relationship with food’. The memoir gives us a story of the food that sustains us – its source, history, production, and its producers in faraway places such as Himachal Pradesh, Meghalaya and Tamil Nadu. The narrative is an adventure that helps readers reaffirm their connection to the planet.

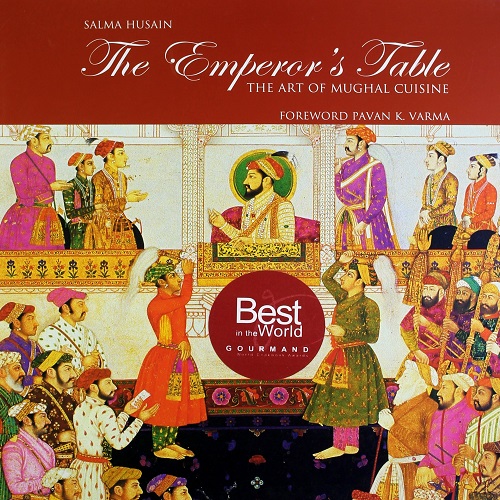

Salma Husain’s The Emperor’s Table: The Art Of Mughal Cuisine challenges the mainstream cultural script by beautifully intermingling food and history. Taking us through the delectable cuisine of the Mughal Empire, the book looks at the Mughal Emperors through their palettes, their favourite dishes and their love for certain flavours. Husain’s book collects recipes from ancient Persian manuscripts, and shows us the evolution of each, as we rediscover the influence of the empire on our everyday cooking. Similarly, Samin Nosrat’s Salt Fat Acid Heat challenges the myth that people only want to understand mainstream food cultures. Her book explains the hows and whys of cooking by using the four most elemental ingredients (mentioned in the title) to highlight how their history can help us explore little-known dishes and cultures.

Food is a remarkable prism through which we are able to see, reflect and appreciate life. The measured and scientific nature of traditional cookbooks are unable to hold space for this narrative around food and memory, which is why, in recent times, we see a dwindling of cookbooks, and an explosion of food memoirs.

We look towards food memoirs as they go beyond particular ingredients, cooking methods and recipes to give us a glimpse into the mind of the authors. They become written souvenirs, as a result – reminders of cuisines, places and experiences that are special. Food memoirs do what cookbooks are simply unable to achieve: they sit at the intersection of food and memory, giving readers something tangible to hold, in the kitchen as well as in life, as the pressure, of everyday existence and the cooker, is slowly released.

Deya Bhattacharya

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!