Feature

The Evolution Of Fairy Tales

“I guess you think you know this story.

You don’t. The real one’s much more gory.

The phoney one, the one you know

Was cooked up years and years ago,

And made to sound all soft and sappy

Just to keep the children happy.”

–Cinderella, Roald Dahl

However embarrassing it might be to admit – but we have all pretended to be the princes, princesses, knights, witches and even horses (cue, me) from the various fairy tales we were told at some point of time in our childhood. These fairy tales, which originated from folklore, have been preserved for many generations through the art of storytelling. Many of us have fond memories of our childhood when our grandparents narrated these tales to us, captivating us with their magical worlds. These fairy tales were whimsical stories full of magic and enchantments, usually featuring brave knights, damsels in distress, mythical creatures and fairy godmother. These stories have firmly established themselves as children’s literature due to the combination of fantasy and moral values found in them.

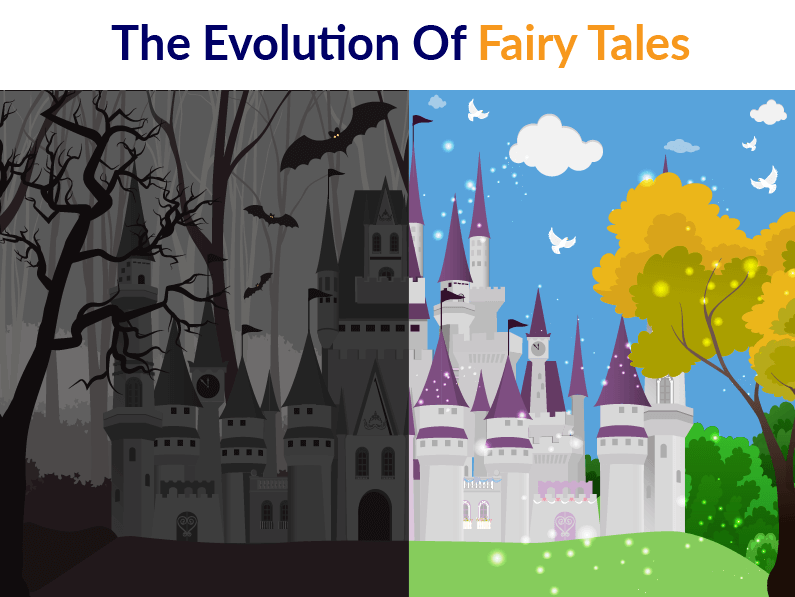

The journey of fairy tales, from oral stories to the written word, has been a fascinating one as there is no account of their exact origin. These stories have evolved from horror-filled narratives to the clichéd versions of a “happily-ever-after” and feminist, erotic and even LGBTQ retellings are currently being written. But how exactly did this evolution occur? How did fairy tales go from being dreadful and scary to flighty and happy? Why are they still welcomed with open arms, even after hundreds of years?

European lore was full of grim tales of torture, murder and familicide. Even though they were filled with the stuff of nightmares, they were advocated as being appropriate for children as they warned them of the dangers that lurked around them. Hansel And Gretel taught children of the peril associated with talking to strangers, lest one turns out to be a witch who wants to bake them. Through Cinderella they learnt that the good prevails and the evil end up punished; Cinderella’s evil stepsisters get their eyes getting pecked out while she is rewarded and becomes a princess. While a lot of European writers assimilated and wrote such grim tales in the 16th century, ‘fairy tale’ as a genre only gained recognition in the 17th century, when Charles Perrault wrote The Tales Of Mother Goose.

Perrault was a French author who lived during the reign of Louis XIV of France. Those were times when good storytelling was considered an art, and the court circles preferred sophisticated and magical tales. In The Tales Of Mother Goose, Perrault changed the violence originally found in folklore to bravery and romance and filled his stories with sly humour, which suited the sensibilities of the French court. Perrault’s versions of Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella are the ones we are familiar today and are also the inspiration behind their Disney adaptations.

Around the early 1800s, the Grimm brothers, Jacob and Wilhelm, wanted to preserve their (and closer to the original) versions of these tales before they were lost forever. They collated tales from friends, literary critics and even drew inspiration from German folklore as a way to capture the essence of the Volk community and published the first edition of their book in 1812.

Education as no longer a privilege of only the upper class, and was compulsory for everyone. As the literate population grew, so did the interest in reading fairy tales. The first edition of the Grimm’s brothers’ book, although named Children’s And Household Tales, was deemed controversial due to the prevalence of rape, murder and torture in the stories. Bowing down to Puritan and the Church’s opinions, the brothers altered these stories and published a second edition, German Legends in 1818, with the horror elements either toned down or cut out altogether. Motherhood was believed to be sacred, so the biological mothers in these stories were adapted into stepmothers, case-in-point– Hansel and Gretel and Snow White. Furthermore, the 18th and 19th century saw an increase in the mortality rate of new mothers, which usually led to children getting saddled with stepmothers, and this was reflected in these tales. The stories themselves were simplified and instead of delving into the complexities of familial relations, they became simple moral lessons on good vs. evil.

The late 1800s and early 1900s saw a lot of publishing houses set up shop, mostly in Great Britain and the U.S.A. But then World War I took place and it led to inflation, and the production of books decreased as resources were rationed. Following World War I, the Great Depression did not help and the demand for fairy tales and books in general went down. However, Walt Disney, well aware of people’s need to escape from a war-torn and economically depressed world, decided to capitalise on the situation and introduced us to an era of fairy tale movies in 1937. With elements of damsels in distress, romance, musicals numbers and formidable villains, these films quickly gained popularity. The “happily-ever-after” theme that is portrayed repeatedly in these films became a norm, and this led to an entire generation dressing up in gowns and armours.

The book industry boomed once again during the post-World War II period, and fairy tales in the form of paperbacks were readily available. People were willing to shell out money to keep their children entertained while instilling moral values of always having hope and good always conquering evil. Fairy tales grew popular as they were mass produced, and became famous, for being both educational as well as entertaining.

(Image via Variety)

The second half of the 20th century, saw a new and more politically aware generation emerge from the war. Due to the approval of the Equal Rights Amendment for Women in 1979, there was a surge in interest of women’s rights and the subsequent atmosphere led to a criticism of the stereotypical themes of knights in shining armour and the portrayal of women as wide-eyed and helpless in fairy tales. Young writers, including immigrants, Jews, African-Americans and women began using literature to make their voices heard. The most noteworthy was James Finn Garner, who published Politically Correct Bedtime Stories, a brilliant satire on fairy tales, one where Little Red Riding Hood lectures the hunter on how she can solve her own problems without any interference and Cinderella decides to forgo her makeover in favour of comfortable clothes. This could have been the stepping stone fairy tales needed to switch from the supposed “traditional” tales to modern ones.

The internet-age brought people closer together than ever before, and by 21st century, a plethora of fairy tales retellings began sprouting up. People continued to hanker for stories that showed little girls that they didn’t have to depend on anyone to be “saved” and little boys that they didn’t have to succumb to the society’s views of what a “man” is supposed to be. In Nikita Gill’s Fierce Fairytales, the fairy-tale retellings empower women to be their own knights-in-shining-armour, to be worthy in their own eyes and to not succumb to societal pressure.

Good Night Stories For Rebel Girls and Stories For Boys Who Dare To Be Different challenge the typical notion that fairy tales should always be about magic and mythical beings. These books narrate stories of real men and women whose success should inspire young kids to be whoever they dream of being. There are also a number of erotic retellings of fairy tales springing up. Anne Rice’s The Sleeping Beauty Trilogy is a study in fairy tale BDSM, and Alison Tyler’s Naughty Fairytales From A To Z are titillating tales that would make the original Cinderella blush. In yet another brilliant and much-needed move, a number of authors are coming up with LGBTQ retellings of Cinderella, Beauty And The Beast, etc., tailored to the queer community. Notable mentions include Girls Made Of Snow And Glass and Ash.

We have covered at least 400 years of fairy tale history, but these questions still remain – why, even after so many iterations, are fairy-tales still relevant? How have they stood the test of time, and why are they still so popular? We can go into the theory of it all we want, but the truth is, no matter what version, fairy tales help reinstate our belief that good will always prevail over evil. Although fairy tales adapt to the changing times, they have still managed to retain their valuable lessons and the wonder of magical worlds. Parents also see them as a way to share a piece of their childhood with their kids – so their kids may experience the same delight they did. Children have vivid imaginations, and fairy tales featuring talking cats, magical mirrors, pumpkins-which-become-carriages and mythical beings appeal to them while challenging their creativity.

When we eventually revisit fairy tales in the future what breakthroughs will await us? Will the princesses have become space fairies? Will the butlers change to robots? Will they talk about global warming or terrorism? Will Elon Musk be portrayed as a brave knight on his mission to Mars? One thing is certain, that these stories reflect our current social conditions and beliefs and should continue to do so. Whatever they might evolve into, it’s fascinating to study these tales that have made been part of our childhood for hundreds of years and are still as fascinating. Whatever else may happen, fairy tales are here to stay.

Do you like fairy tales? Have you read any of the original versions? Have you read any alternate versions? Which version do you prefer? Share with us in the comments below.

Prasanna Sawant

Prasanna is a human (probably) who makes stuff up for a living. When she's not sleeping or eating, you'll find her in the quietest corner of the library, devouring yet another hardbound book. She vastly prefers the imaginary world to the real one, but grudgingly emerges from her writing cave on occasion. If you do see her, it's best not to approach her before she's had her coffee.

She writes at The Curious Reader. You can read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!