Feature

How Margaret Atwood Redefined Mythology Through Her Feminist Retellings

“Every Myth Is A Version Of Truth”

– Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood is brilliant at everything she does – whether it’s writing dystopian or science fiction, campaigning for animal rights, or spending time on her art. A staunch feminist and a gifted writer, Atwood is popularly known for her dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale. Ardent fans of Atwood, however, know that she has also dabbled in mythology quite a bit, and many of her works, both prose and poetry, reflect that. Basing her stories on famous characters from classic mythology like Penelope, the Sirens, Sekhmet, and Circe, she’s criticised contemporary patriarchy and given a voice to women who are often portrayed as eternally submissive. Raising pertinent questions about classic mythology, such as why they are mostly written from the male perspective, and why abused mythological women remain unheard, Atwood seamlessly weaves them into contemporary society and gives these women the platform they were denied in their original stories.

Penelopiad

In most classic mythologies, women are often portrayed as either negative characters or passive aides to the heroes who get all the glory. Contemporary poets like Atwood have begun retelling these myths by viewing them from a feminist perspective, thereby highlighting the stories of women living in the shadows of men. In Homer’s Odyssey, the fame entirely belongs to Odysseus. He hangs his maids for socialising with his wife’s unwanted suitors. His wife Penelope dutifully remains in the background, quietly waiting for her husband. Atwood spins a different version of the classic mythology wherein the clever Penelope is finally given her due.

In Penelopiad, the short novella from the Canongate Myth Series, Penelope is not just Odysseus’ docile wife, but a clever ruler as well. While her husband is away at war and on other adventures, Penelope learns to manage their kingdom and its trades, and devises a clever plan of weaving her father-in-law’s shroud to keep her pesky suitors away. The Penelope of Atwood’s Penelopiad is now able to tell her tale from the Underworld, as she is now dead. In death, she becomes free of her worldly woes and responsibilities and cannot be judged or insulted for anything she does, which grants her the freedom to convey her innermost thoughts. Even the 12 hanged maids make an appearance, in the form of songs and ballads, which portray how unjustly they were raped and then hanged, all because of their position in the social hierarchy. Atwood’s Penelopiad is not just a sad tale of women, but a critical commentary on a society that treats them as nothing more than props in a man’s world, and those from lower economic classes as disposable.

Morning In The Burned House

The patriarchal society we live in has different rules for judging men and women, viewing everything women do through a hypocritical lens. Mythology is an extension of this unjust society, where a woman is supposed to behave a certain way, and is always blamed, even when she is not at fault. In Greek mythology, Helen of Troy is hailed as the ‘most beautiful woman’, and was often judged for indulging in affairs and starting the Trojan War. In Atwood’s collection of poems, Morning In The Burned House, Helen moonlights as a stripper and revels in the power her sexuality brings her instead of feeling guilty over it. She questions her audience, her “beery worshippers”, as to what classifies jobs as degrading or respectable. The Helen in Atwood’s poetry knows beauty is power and defies societal expectations by not conforming to the norms of a more standard 9-5 job.

The poem ‘Daphne And Laura And So Forth’ centres around Daphne, who Apollo fell in love with and was turned into a laurel tree to avoid becoming a victim of Apollo’s unwanted advances. Atwood mocks today’s society that blames a woman for showing too much skin, a blatant and utterly foul excuse for men’s despicable behaviour with the verse “I should not have shown fear, / or so much leg”. When Atwood’s Daphne is turned into a spider, she begins weaving ideas and means to get her revenge. She is no longer a victim, but a survivor. In a society steeped in patriarchy that expects women to be either warm-hearted and kind or wilful and wild, a woman who effectively balances such traits is confusing, to say the least.

In the poem ‘Sekhmet’, Atwood voices Sekhmet, an Eyptian goddess of both war and healing.

I just sit where I’m put, composed

of stone and wishful thinking:

that the deity who kills for pleasure

will also heal,

These lines from the poem suggests how our male-driven society expects women, even warrior goddesses, to heal while giving them no respect whatsoever. Atwood proves how Sekhmet is inherently neither good nor evil, but manages to combine both those qualities seamlessly without having to change herself. Atwood’s Sekhmet is fierce yet kind, human but also an animal, and balances both feminine and masculine qualities effortlessly. Yet Sekhmet is unabashed in saying that she is a fierce goddess first and foremost, and should not be crossed. This is crucial, as it expresses how some women are expected to be submissive and their apparent “wilful” behaviour must be curbed.

(Image of Margaret Atwood via Monday Magazine)

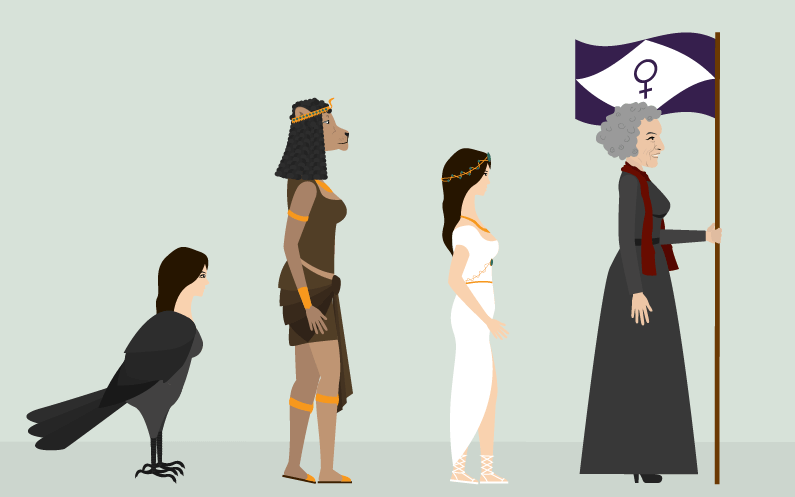

You Are Happy

In classic mythology, vilified women rarely find a place for their own narrative. Even if they do, it’s usually limited to a plea for help. Atwood’s ‘Siren Song’ from the poetry collection You Are Happy is one such place where the apparent villains of Greek mythology are finally given a voice. The Sirens are half-bird, half-woman creatures who lure sailors with their enchanting voices and devour them. Atwood’s Sirens own their villainous nature, and are not defined by their power, but rather by how their power affects men. This poem is a clever play on the “damsel in distress” stereotype, wherein the Sirens use their cunning to play the distressed damsel and lure men to their deaths.

In one section of You Are Happy titled ‘Circe/Mud Poems’, Circe, a vilified sorceress is both – a victim of patriarchy as well as a creator of an alternative feminist narrative. Her love for Odysseus implicates her in the gender war and forces her into becoming just another notch on the bedpost in the male narrative. But when the travellers tell her of a woman they made out of mud and slept with, and how “no woman has since equalled her”, she ponders, “Is this what you would like me to be, this mud woman? Is/this what I would like to be? It would be so simple.” Here, she realises how easy it might be to just be a body for pleasure, but she is more than that. Atwood’s Circe is a not a mud woman, but a person in her own right, and coming to this realisation, she lets Odysseus leave, instead of moulding herself into the version he demands of her.

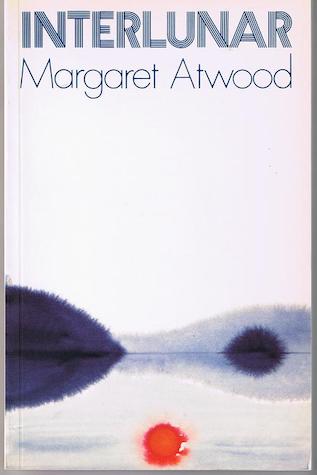

Interlunar

Having grown up with classic mythology that doesn’t always shine a light on feminist issues, it becomes harder to unlearn the submissiveness that these myths impose on us. It is only through writers such as Atwood that we start to question the traditions of a patriarchal society and begin to see the female perspective as well. A brilliant example of this is the various mythological retellings in the poetry collection Interlunar. The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice is well known, where Orpheus, who can even charm stones with his music, brings his wife back from the Underworld by charming the lord of the Underworld. But, in the original myth, Eurydice has been given no voice to tell her tale, no mention if she loved him or if she even wanted to leave the Underworld. As always, women remained hidden in the shadows of the great heroes, and their voices remained unheard. The myth of Eurydice and Orpheus has been romanticised, but Atwood shows us that there could be a different version to this romantic tale.

‘Orpheus 1’ tells this tale from Eurydice’s perspective, where Atwood suggests that Orpheus is physically dominating, and Eurydice says that she would rather be in hell than return to the living world. Orpheus refuses to believe that she could be anything other than his “echo”. Here, Orpheus, like many men, is projecting his own ideas as to the kind of a woman Eurydice is required to be. In death, Eurydice says, she is her own person, an independent individual who doesn’t have to fit herself into Orpheus’s idea of her. Even in the poem titled ‘Eurydice’, there are mentions of how Orpheus loves something that does not exist anymore and tries in vain to reclaim the woman of his imagination instead. While men constantly try to mould women in their own ideas of the ideal woman, these retellings are a way for these strong women to make their voices heard.

(Image of Sirens via Audubon)

In a society that is steeped in toxic patriarchy, writers like Atwood present a new perspective on feminism using male-centric classic mythology. For Atwood, such myths can be used to tell living truths, showcasing the full range of human desires and fears. By criticising the influence of myths on people and adding new perspectives and possibilities, Atwood brings a new approach to how women should be perceived in the fight against toxic masculinity. It is time we learn to unlearn such one-sided myths and actively strive to look at the female perspective. In a man’s world, let us make it a mission to carve out our own identity, and maybe, just maybe, by doing so, the tragic females of mythology will finally get their due.

Which of these feminist retellings of classic mythology by Margaret Atwood have you read? What are your thoughts on them? Share with us in the comments below.

Prasanna Sawant

Prasanna is a human (probably) who makes stuff up for a living. When she's not sleeping or eating, you'll find her in the quietest corner of the library, devouring yet another hardbound book. She vastly prefers the imaginary world to the real one, but grudgingly emerges from her writing cave on occasion. If you do see her, it's best not to approach her before she's had her coffee.

She writes at The Curious Reader. You can read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!