Feature

Where Is Hindi Literature When It Comes To Screen Adaptations

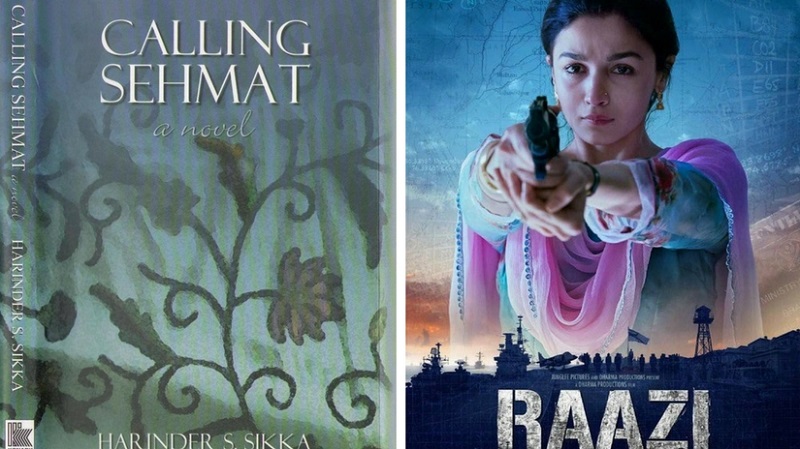

What do Sacred Games, Leila and Calling Sehmat have in common? They’ve all been adapted for a TV series or a movie in recent times. Bibliophiles rejoiced as Indian literature was given the attention it deserved. But, take a closer look at the language these books were originally written in. They’re all examples of Indian literature written in English. Which makes us then wonder – where is Hindi literature when it comes to adaptations? Why are those books not getting picked up like their English counterparts?

In a country where more than 400 million people speak in Hindi, it is surprising that Hindi literature is scarcely used as material for adaptations. Considering the rich legacy of Hindi literature, this gap is flummoxing. While streaming services and the Hindi film industry have seen a rise in contemporary books being adapted, almost all of them are in English. This World Hindi Day, we examine why there is such a dearth in Hindi literature being adapted on-screen.

Golden Age Of Hindi Literary Adaptations

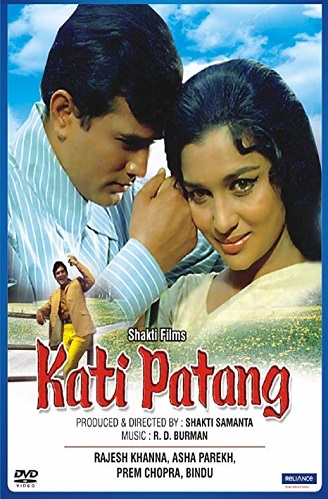

The period during and after Independence saw Hindi literature flourish, with authors like Kamleshwar, Munshi Premchand and Bhisham Sahni presenting the world with some of the most compelling and heart-wrenching stories ever written. This was also a time when people needed uplifting stories of heroism and romance, and what better way to adapt these stories on to the big screen? Films like Chitralekha, Kati Patang and Pati Patni Aur Woh were all adapted from some of the most stunning works of Hindi literature, and gave the people recovering from the ruins of Partition, a positive and, in the case of Pati Patni Aur Woh, a comical look at life.

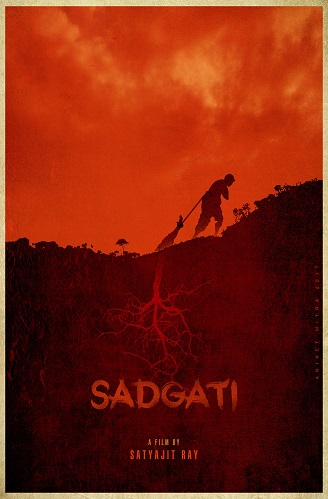

Authors of that time wrote extensively about the issues that plagued our society, including caste discrimination, inequality and poverty. As the popularity of the visual medium increased, it led to books based on social issues getting adapted into movies which, in turn, paved the way for an increased awareness about these topics within the country. Films like Satgati and Tamas portrayed the stark realties faced by the people. These gut-wrenching stories, when portrayed realistically on screen, led to a deeper relationship between films and Hindi literature. Movies based on such hot and relevant topics were liked by the people, and Hindi literature was in its Golden Age.

Rise Of English

Over the last few decades, the Indian education system has gradually shifted its attention to English. Due to the impact of globalisation and the increasing reach of a social media-friendly world, English has become a popular mode of communication across the country. As a result, for most of us, Hindi has become a subject to be studied only in schools since children today are choosing to use English to communicate. English is now spoken by over 256,000 people in the country.

Sidharth Jain runs The Story Ink, a company which helps authors to sell their stories to filmmakers. He says, ‘The Bollywood film industry is based in Mumbai, where English is the prime language of communication. The industry relies on English, and in today’s world, English is an accessible language. As people are coming from varied places with different mother tongues, English unites them.’

Gaurav Solanki, who co-wrote the acclaimed film Article 15, says that a lot of filmmakers also don’t read books written in Indian language. Sidharth adds, ‘Most of the scripts for films are first written in English, even for the Hindi movies. As such, a book written in English is easier to adapt than its Hindi counterpart. If someone actually wants to adapt a Hindi novel, they have to hire a Hindi reader, and a screen writer to adapt the story. This makes the process a bit more tedious, especially when a number of brilliant English books are in the market.’

This adds another point to the list of reasons related to the dearth of Hindi literary adaptations and paints a rather bleak picture for its future.

(Image via IMDb)

On The Publishing Side

The responsibility of adapting Hindi literature does not solely lie on the shoulders of the film industry and streaming services. Publishers and writers also don’t seem to be very interested in seeing their books being adapted for the big screen. At a time when content is available in plenty and OTT platforms are actively looking for material to adapt, it is the duty of Hindi publishers to study the Hindi film industry and the OTT platforms, and form strategies to help their authors’ works get picked up for this process. Unfortunately, this still remains at a rather nascent stage in India.

Given that The Story Ink works with a lot of publishers and authors to get their books adapted for films, Jain agrees that the publishing industry has a lot of catching up to do. He says that there is a huge growth opportunity for them in this era of Internet, but they seem to be unaware or uninterested in using it for their benefit. He was at MAMI’s Words to Screen initiative in 2019, which provided writers with a platform to sell their books to filmmakers. Although there were a few Hindi publishers at the event, he says only one person approached him with ideas.

Solanki shares the same opinion when he says that although many production houses are actively looking for Hindi literature, the publishers and authors should also make an effort to ‘bridge the gap’. Even the co-writer of the film Stree, Raj Nidimoru agrees that the Indian film industry is severely lacking Hindi literature. He sums it up by saying, ‘There is a depth in our literature but unfortunately we seem to overlook it. It is time we start looking at [Hindi] literature and we have such great stories to tell.’

Contemporary Hindi literature has a number of wonderful books available like अकाल में उत्सव (Akaal Mein Utsava) , हलाला (Halala), दर्दजा (Dardja) and लाल लकीर (Laal Lakeer). They focus on delicate and important issues of society, such as the oppression of women, genital mutilation and Naxalism. While people do want to see films based on such topics, the audience is still limited. Pradeep Sarkar, who adapted Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s famous novel, Parineeta, says, ‘The new generation of filmmakers is “fast-moving” but in the race to make “edgy films”, something is being left behind.’

(Image via Firstpost)

Commercialisation And The Era Of Sensational Films

Today, people are more interested in watching a potboiler film filled with goons, damsels-in-distress and a plot that solely focusses on action. During such times, OTT platforms and the film industry, thinking of their profit margins, capitalise on this audience and release multiple films that follow the same format. Only a few focus on details like an intricate plot and a good story. The audience are interested in destressing, and compelling and entertaining commercial films and TV shows help them with it.

But, if action-packed films are the norm today, why aren’t we looking at Hindi pulp fiction novels? They are quintessential Bollywood commercial film stories – action-packed thrillers or mysteries, with damsels, and macho heroes ready to save the day. Authors like Surendra Mohan Pathak and Ved Prakash Sharma have an abundant repertoire of these stories, so why is the film and television industry not using them?

(MAMI Word To Screen; Image via The Hindu)

Today, Hindi literature appears to be lagging behind in the race with English books when it comes to literary adaptations. The responsibility to not let Hindi be a thing of the past is now on our shoulders. As readers, we have to actively seek out Hindi literature. Only then will we see how rich our language and its stories are. Filmmakers also need to turn towards our Hindi books for stories, as there are many hidden gems just waiting to reach more people via adaptations.

But, the most important work lies in the hands of publishers and authors. Both need to work harder at not only promoting their stories, but also ensuring that their works reach the big screen, and, subsequently, more people. Maybe a combined effort is what is needed to make Hindi literary adaptations relive the Golden Age once again.

Prasanna Sawant

Prasanna is a human (probably) who makes stuff up for a living. When she's not sleeping or eating, you'll find her in the quietest corner of the library, devouring yet another hardbound book. She vastly prefers the imaginary world to the real one, but grudgingly emerges from her writing cave on occasion. If you do see her, it's best not to approach her before she's had her coffee.

She writes at The Curious Reader. You can read her articles here.

I agree. A poignant piece.