Feature

Carving Space For The Unheard Narratives Of Marginalised Womxn

Note: The author uses the word womxn within this piece to be inclusive of the spectrum of sexual and gender identities. Inclusion in language begets inclusion in literature.

Does our present literary culture hold space for all people? Does the construction and interpretation of mainstream literature often other non-mainstream cultures and communities? And does this deliberate or inadvertent othering mute and silence some narratives, while aiming to do the opposite? How can we articulate such narratives of unheard, unspoken voices within the current but limited framework of mainstream literature? These are some questions I grappled with as I attempted to understand our access to literature and language today. These are also significant questions that should be posed to the gatekeepers of the Indian literary scene.

Language, and by extension literature, often alienates the unheard narratives of marginalised womxn. Non-cisgendered, trans, non-binary, queer, Dalit, and disabled narratives often go unheard as the texture of the literary landscape looks and feels out of reach because of this underrepresentation. When lived realities don’t find a place in mainstream literature, it stands to further devalue and dehumanise certain womxn, resulting in multiple marginalisation. Therefore, it is significant to acknowledge the ways in which that current literature silences certain voices, and how we can work towards foregrounding these narratives.

Minor Literature And Marginalised Womxn

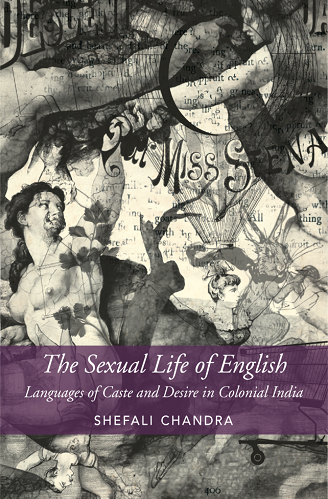

To understand why narratives of marginalised womxn are often left out of the mainstream literary culture, especially in India, it is significant to learn and understand the place that English as a language occupies.

In her book The Sexual Life Of English: Languages Of Caste And Desire In Colonial India, Shefali Chandra talks about the superiority of English as a language in both colonial as well as present-day India. She speaks of the ways in which colonised Indians were convinced that ‘English [was] complete in all its useful and entertaining elements, and adequately expressive of individual thoughts, feelings and wants’. This created a hierarchy between the colonists’ language and our own. It is this disciplinary and phallocentric nature of English that deliberately keeps non-English speakers and writers out of the literary space. Or worse, their work is subject to over analysis and interpretation. This is a demonstration of power that relegates non-English speakers and writers to the margins and silences their voices.

This is the reason why comprehending the concept of minor literature is significant. According to Deleuze and Guattari, ‘a minor literature is not the literature of a minor language but the literature a minority makes in a major language’. Minor literature is political; even individual narratives are plunged into the political, and it has collective value.

Ruby Hembrom’s work with her Calcutta-based publishing house, adivaani, has aspects of minor literature. Hembrom is the first and only Santhal publisher who has been recording unheard, indigenous voices, and showcasing them adjacent to mainstream literature. She chose to publish in the major language of English as a form of protest. adivaani’s work is feminist and is an attempt to carve a place for minor literature within the mainstream literary community. Minor literature, therefore, is rebellion. It is evidence that literature can in no way escape the realities and power structures of our quotidian lives.

Writing As Righting

Meena Kandasamy, a Dalit-feminist writer and poet, has said that ‘[P]art of writing is to open up wounds.’ The function of unheard, unspoken narratives by womxn from marginalised communities is to propel change and drive movements, while gradually eroding at traditionally established literary boundaries. In essence, the writers of unheard narratives, the ones who strive to bring these stories to the forefront, are engaging in rights-based work, while struggling to access the knowledge and social mobility that the publishing industry brings.

In an interview, Kalyani Thakur Charal, well-known Dalit feminist poet from West Bengal, talks about what writing means to her – ‘For me, writing poems is participating in cultural movement. I write poems to register my thoughts and feelings. It does beyond the literary boundary. My poems address social issues. They are the poetics of age-old oppression against the Dalits.’ Her autobiography in Bangla titled Ami Keno Charal Likhi (Why I Write Charal) compares her time working in a traditional government office with Sita’s trial by fire in the Ramayana. The various books and journals published by Kalyani are about a plethora of topics including Dalit folklore and poetry, their attempt at reading and writing, short stories on famous Dalit womxn activists, to water crises in the world as well as Bangladeshi refugees.

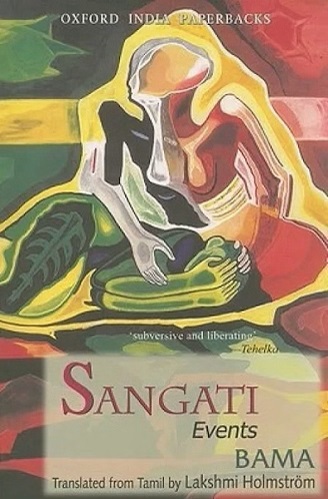

From Tamil Nadu, Bama Faustina Soosairaj, a pioneer of Dalit feminist literature, wrote Sangati, a novel that can be described as an autobiography of a community. The story deals with the personal and private narratives of Dalit womxn, charting their social identity as well as their struggles towards transformation. The format of Sangati is not like a mainstream book of short stories or essays – the stories are not linear, the events do not seem episodic and some characters are banal stereotypes, and yet, Bama is able to show us the realities of Dalit womxn. Her other work, Vanman, talks about the atrocities by the police against the womxn of Parayars.

Kandasamy’s poetry is about the empirical truth, power and autonomy. In an interview, she acknowledges that she chose poetry deliberately, as a medium, as ‘poetry is intricately connected with language, and since language is the site of all subjugation and oppression, I think poetry alone has the power of being extremely subversive.’ Kandasamy’s understanding is that her narratives will be heard through poetry because that is how she offers up her resistance:

‘I dream of an english

full of the words of my language.

an english in small letters

an english that shall tire a white man’s tongue.’

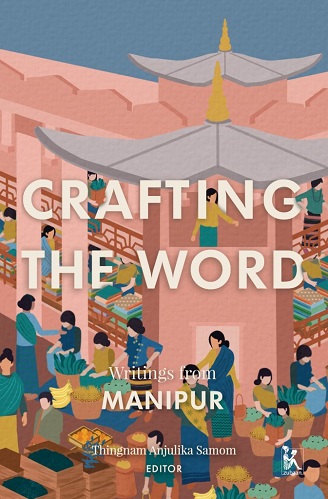

Some books published by Zubaan Books, the feminist publishing house, also highlight unheard womxn’s narratives, alongside other literary and academic content. This is because they publish fiction and non-fiction that transcend conventional rules of literature and explore obscure thematic areas that are rights-based and feminist. A few of their books that mandate mention are Thingnam Anjulika Sanom’s Crafting The Word: Writings From Manipur, a collection of feminist writings from Manipur by a group of womxn writers, highlighting their activism at the forefront of peace-building in a region ravaged by armed conflict; and filmmaker and writer Anungla Zoe Longkumer’s The Many That I Am: Writings From Nagaland, a collection of short stories, poetry, first-person essays and visuals about the journey of womxn to reclaim their past, portraying the culture of the Nagas, who had no tradition of written language before the Church introduced it.

Blurring Conventional Lines In Fiction And Real Life

Unconventional narratives of womxn from marginalised communities also defy traditional rules and customs, of both language and gender roles. Existing frameworks and tropes of mainstream literature and politics have been rendered inadequate as they do not represent marginalisation. These identities exist in an intersection, and tropes from mainstream Indian literature are incapable of adequately capturing such nuances.

For instance, mainstream Indian literature is cultivated on the public/private divide – narratives highlight brave men fighting in the public sphere, while beautiful, sensitive women hold up the household in the private sphere; their lived realities situated only in these respective spheres, entrenching gender roles and biases. Non-mainstream narratives take the public/private divide apart completely, implying that a Dalit, queer, trans, disabled womxn has mobility in and out of each sphere, but both spheres may be equally inaccessible, violent and exploitative for marginalised and intersectional identities. Kalyani Thakur Charal’s poem no. 33 from Chandalinir Kobita puts forth this idea:

‘My grandfather was prohibited

From stepping into the tol premises.

My father became literate

Using palm leaf and ink of charcoal

After a long struggle.

My mother visited Durga bari

With cow dung on her left hand

To paste the place where she was standing.’

Besides blurring conventional lines within academia and activism, such unheard narratives also distort the rules of fiction, writing and storytelling, while deconstructing the modern novel, essay or memoir. One such book is Kai Chen Thom’s Fierce Femmes And Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir, which is a sort of a bildungsroman of massive proportions told through the landscape of mythological archetypes and fairy tale wonder. The Chinese-Canadian trans-woman writer draws up a fictionalised memoir that is populated by anthropomorphic characters that function as exaggerated reflections of reality, thus compelling readers to explore the complex lived realities of a trans person in the comfort of a fantastical world.

Other books such as Motherwit by Urmila Pawar and These Hills Called Home: Stories From A War Zone by Temsula Ao tell the stories of common people, mostly womxn, who have been survivors of caste oppression and victims of war respectively. These books focus on telling the stories as they are – they do not embellish or exaggerate; they seek and tell stories from the grassroots, because that is where the movement is, as opposed to mainstream literature that glorifies only luminaries.

Merely understanding the role of silenced or unheard narratives is not enough. The present literary landscape is obligated to look beyond what it deems as literature – writing is not the only way to document narratives, and English is not the only language that should be used.

There are thousands of tribes within India, with their own languages and dialects and their narratives that are passed on through generations orally. The idea, essentially, is to radicalise the ways in which we view literature – making it inclusive of people, identities and formats. Another way is to provide more visibility to marginalised womxn writers by publishers through social and other forms of media. This would result in easing access of readers towards minor literature and provide recognition to these writers. Lastly, the idea is to be open, as opposed to rigid – open to understanding the ways in which our own biases and prejudices, in the real world, make it challenging for us to reach out towards the works of marginalised womxn writers.

Deya Bhattacharya

Deya is a human rights lawyer by day, and by night, a book nerd, who is constantly running out of shelf-space. Her small apartment in Bangalore, where she is based, has already been swallowed by her meandering bookshelves. Truth be told, this might also be her ultimate plan to avoid all human contact. Deya tweets about feminism, women's rights and (mostly) all things books at @LadyLawzarus.

Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!