Feature

Musing Over Murakami And Spaghetti

Phorum Dalal

December 4, 2017

When we read a Murakami book, life slows down every time a character decides to make spaghetti. As readers, our mouths water as the slender pasta is dunked into boiling water, the steam rising and fogging our spectacles. I always picture an empty house, pin-drop silence, and bright red tomatoes lying on a wooden chopping board.

While the words focus on the activity of cooking, Murakami uses them to stealthily weave in nuances of the character – lonely, stubborn, meticulous, grey, or dreamy.

Pasta In The Pages

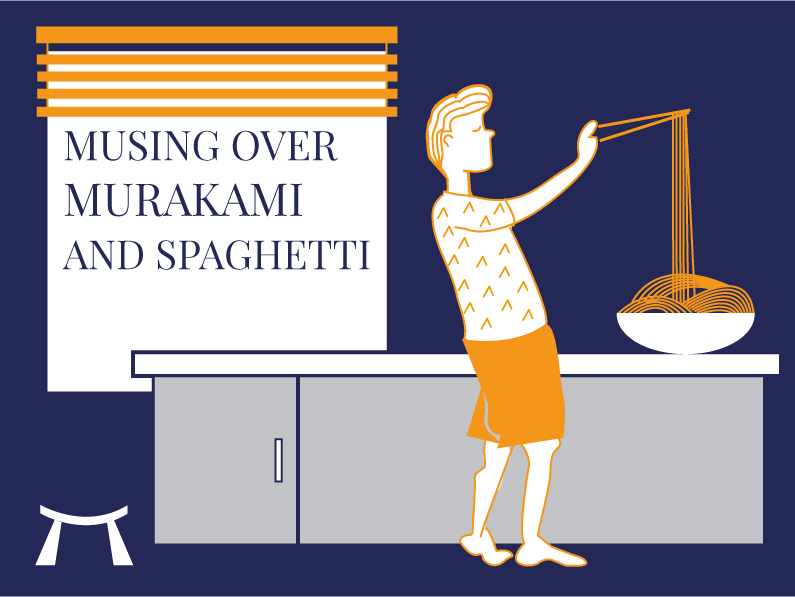

In The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, the protagonist is “boiling a pot of spaghetti” in the kitchen, when the phone rings. He wants to ignore the phone, not only because the spaghetti is nearly done, but also because Claudio Abbado is bringing the London Symphony to its musical climax.

Expecting to hear about a job, he gives in, turns down the gas and makes his way to the living room to pick up the receiver.

If you are a Murakami reader, you can guess what will happen next- one thought will lead to another, until you find yourself immersed in a web of his words, holding onto every word, every nuance, and every sentence that has become a reader’s delight.

The woman, on the other end, asks for ten minutes. In the protagonist’s head, it’s too much; his spaghetti will over boil. He begs to call back, but she resists. The protagonist is caught in a dilemma here: should he risk overboiling the pasta or discover why she called.

But Murakami has thought it all through. He has a plan. Spaghetti takes the form of a long comma; at times a veil on the events to follow. As readers, we creep to the edge of our seat. The phone call ends abruptly and the spaghetti is left a little over al dente.

History Class

I turned to a chef to study the nature of spaghetti, hoping to better understand Murakami’s obsession with it.“According to history, spaghetti was first mentioned in the Talmud in 5th century A.D.,” Italian chef Davide Cananzi tells us.

Rumour has it that Marco Polo introduced pasta to Italy from China, but it is just a misconception. In an episode of the podcast “Stuff You Missed In History Class”, titled “The Marco Polo Pasta Myth”, we learn that he did bring back some macaroni from China. The first recipe of pasta, which used millets, can be attributed to the Chinese and goes back 4000 years.

The question arises, “Who came up with pasta first? Was it the Chinese, the Arabs or the Italians?” The correct answer is China. Italian pasta was inspired by the Arabs, who had their own kind of pasta made from durum wheat.

When Cananzi gives us a technical deconstruction of pasta, we cannot help but think of Murakami’s writing. Due to its shape, spaghetti has an incredible ability to blend well with all types of sauces (and thus, all types of situations in a Murakami world). However, pairing it with tomato is usually preferred (even by his characters).

Cananzi says that it is very important not to overcook spaghetti. In just over 8 minutes, it releases starch and will turn into a glutinous mess. Well-cooked pasta will not break when its mixed with the sauce. In the same way, pasta plays a crucial role for Murakami, stepping in to support the protagonist at the exact hour, for just the exact amount of time; and making an exit just before the moment loses steam.

Easy Peasy

For a second, let’s take a closer look at spaghetti – an easy dish to rustle up, a comfort dish. A bowl of spaghetti looks like a woven mesh, sometimes a messy chunk and sometimes a well-spun ball. We make our own mess, and we iron out our own shortcomings.

Spaghetti is also a community dish that cuts across classes, and no one really makes spaghetti for one. But in Murakami’s settings, the character almost always makes it alone – twisted in own maze, like the strands entangled in your bowl.

Everyone who cooks pasta in his stories is in deep-thought mode, sometimes making the reader wonder whether they are intruding on the character’s home or mind space. Spaghetti becomes Murakami’s tool to set moods, to stretch a moment, to distract the reader and create a comfortable monotony that eases the reading process. If you take the bait, he will lead you through the labyrinth that is the mind of the character. Murakami relies on spaghetti like a tarot reader does on her cards, an astronomer on his telescope, and a singer on her voice.

In Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman, a short story titled “The Year Of Spaghetti” is dedicated to spaghetti. The narrator calls 1971 the year of spaghetti. “I cooked spaghetti to live and lived to cook spaghetti. Steam rising from the aluminium pot was my pride and joy, tomato sauce bubbling up in the saucepan my one great hope in life.”

The narrator goes to a specialist cookware store and brings home a kitchen timer, the aluminium pot, spices, a pasta cookbook, and every brand of spaghetti he can lay his hands on, to cook them in “every kind of sauce known to man.”

From this behaviour, we gauge he is a veteran- an expert at cooking and consuming spaghetti. Spaghetti is his confidant, one who accepts his shortcomings, his monotony, and his reasoning. Interestingly, he likes to devour it alone, for he is convinced it is the only way to enjoy it – while sipping on tea and digging into a side of lettuce-and-cucumber salad.

For him (and many of Murakami’s other characters), spaghetti is a way of life, and he cooks it through spring, summer, and autumn, “as if it were an act of revenge.”

Pasta As A Metaphor

Let’s move on to a short story from The Elephant Vanishes. In Family Affair, a brother-sister duo shares an apartment, and whether they like it or not, they share their lives too.

“At the time we were talking about spaghetti. She was telling me that that I had a narrow view of spaghetti. This was not all she had in mind, of course. Her fiancé was lurking somewhere beyond the spaghetti, and she was really talking about him.”

This is a clear example of how relatable and human Murakami’s characters are. When they want to avoid confrontation, they will find ways and means to express their opinions without really saying them.

The story goes on, “The problem started with the spaghetti itself, which was a disaster. The surface of the pasta had an unpleasant, floury texture. The centre was hard and uncooked. Even a dog would have turned its nose up at the butter they had used. I couldn’t eat more than half of what was on my plate, and I asked the waitress to take the rest away.

My sister glanced at me once or twice but didn’t say anything at first. Instead, she took her time, eating everything they had served her, down to the last thread. I sat there, looking out the window and drinking another beer.”

There’s a defiance in the sister’s act of finishing her underwhelming meal, while the narrator refuses to eat it. The sister is here to make things work, while the narrator makes no attempt to entertain anything that doesn’t appeal to him.

Wingman Role Play

What does the symbol of spaghetti mean to the author? Every time it appears in a scene, as a reader, I get the feeling of catching up with an old friend. Since, it’s a Haruki Murakami book, of course, I expect spaghetti to play a role. Murakami’s stories are bizarre, contemporary masterpieces; with spaghetti adding a known touch. It eases the reader even in uneasy situations. The slimy strings mixed with a sauce, offer the perfect comfort meal.

In a way, this dish is Murakami’s wingman. It helps him show his characters in the best possible light. And to us, dear readers, it is a familiar and comfortable object- like a T-shirt we’ve worn too many times- in his unpredictable story world.

Have you noticed how Murakami uses spaghetti in his stories? Are there any other recurring motifs, which you associate with Murakami? Let’s discuss!

Receive articles like this in your inbox. Subscribe to our weekly newsletter and get the best of what to read from around the web.

Phorum Dalal

Phorum Dalal is a Mumbai-based food, travel and lifestyle journalist.

This article is so beautiful. The opening reminds me of a Miyao Hayazaki or an anime film. It did make me hungry because of its visual description. I have not read a lot of Murakami but will surely now notice whether he depicts spaghetti the next time I pick up his books.