Feature

Naipaul And Theroux On India: A Critique

Kerry Harwin

February 06, 2018

“You make up your minds about India before coming to the country. You’ve been reading the wrong books.”

An Area of Darkness – V. S. Naipaul

“6 is okay?” he asked, hopefully.

It was neither a question nor a statement. It was an opening bid in a negotiation. The guesthouse manager was gone for the weekend, leaving the cook as the most senior staff member. And, following the grand human tradition of cutting out early when the boss is gone, the cook was trying his luck with potentially gullible foreign tourists.

“No,” I said. “We can manage 7.”

Agreement was quick; 7, it seemed, still counted as a win as far the cook was concerned. But my mother, perhaps incited by the cook’s thin, sinewy, sarong wrapped body, a shock of white hair topping his equally white, rheumy eyes, interjected: “No, no, 6:30 will be fine.”

The cook quietly receded into the kitchen, careful to coat his smashing victory in a patina of mild defeat.

We were on a family trip across India and Sri Lanka, my parents and an aunt in from the United States. I had lived in India for nearly a decade, while they had just arrived on their second trip. Returning to the dining room, I insisted that it would really be okay if we wanted to have dinner at 7, or even 8.

“You’re acting like such a stereotypical ugly American,” my mother told me, no attempt made to disguise her disdain.

The rest of the family piled on: “You think that no matter how far from home you are, you deserve to get exactly what you want, when and how you want it. And you don’t care who you step on along the way.”

Continuing to press my case would have done it no good. But time would confirm my initial appraisal of the situation. A conversation with the manager cleared up the dinner timings (until nine at least) and, when domestic tourists arrived at our guesthouse two days later, the cook served their meal several hours after our respectfully early dinner hour.

But my family had no interest in this new information. My inability to let the matter rest merely fueled their anger.

My family and I were engaged in an argument that has been ongoing since roughly three centuries before Jesus Christ is said to have been born.

It is an argument that has continued since Megasthenes, Greek historian and Ambassador to the Mauryan court became the first known foreigner to attempt to understand the subcontinent and explain it, in writing, to the rest of the world. And it is an argument often rife with ignorance and preconceptions.

In the 1960s and 1970s, when the Beatles were discovering India and the rest of the switched-on world was following their lead, as India was easing herself out of centuries of foreign rule, a new batch of foreign explainers arrived in the country.

Most notable among them were V. S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux. Naipaul, a Trinidadian of Indian descent, was then an up-and-coming novelist in his late twenties. Theroux, the American novelist, and essayist, who would later engage in a public enmity with Naipaul was, at the time, a mentee of the famous Trinidadian. Both would carry their preconceptions along with them as they attempted, in Naipaul’s An Area of Darkness and Theroux’s The Great Railway Bazaar, to translate India for the outside world.

In The Great Railway Bazaar, Theroux narrates a year-long round-the-world train journey, from London through Istanbul, down to Madras and Sri Lanka, back up through Burma to Southeast Asia and, with the help of a few boats and planes, through Japan to Siberia, finally traversing the Soviet Union to return to London. Nearly a third of the work is devoted to his time in South Asia where, in a narrative that rarely escapes the confines of the Indian Railways, he forms grand conclusions about India and her people.

“I have seldom heard a train go by,” Theroux writes in his opening line, “and not wished I was on it.” This is our only explanation for Theroux’s choice of exploration from inside a railway berth. Rarely stepping far from the train or the station, he views the railway as a microcosm, representative of entire societies. Upon his arrival in India, at Amritsar Station, he makes this explicit:

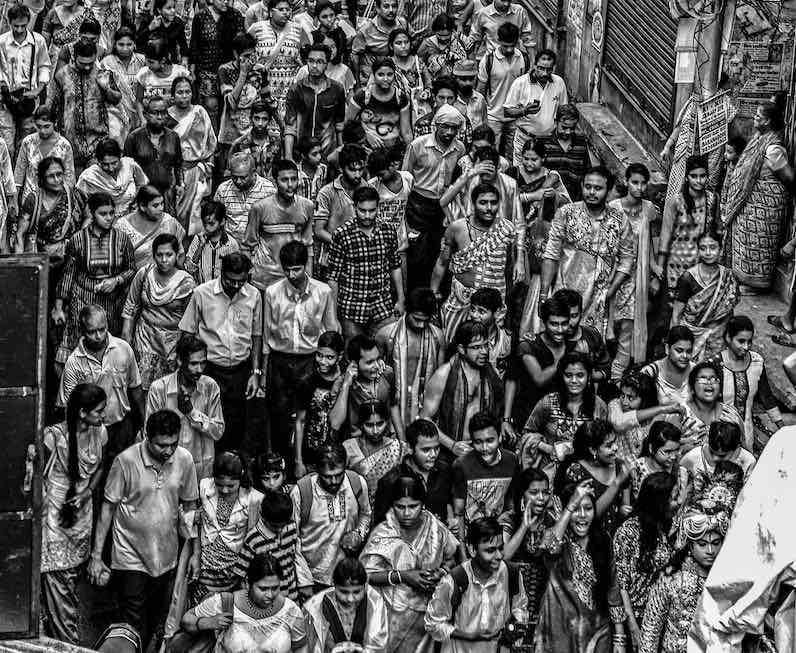

To understand the real India, the Indians say, you must go to the villages. But that is not strictly true because the Indians have carried their villages to the railway stations. …The newcomer cannot believe he has been plunged into such intimacy so soon. In another country, this would all be hidden from him, and not even a trip to a village would reveal with this clarity the pattern of life. The village in rural India tells the visitor very little except that he is required to keep his distance and limit his experience of the place to tea or a meal in a stuffy parlour. The life of the village, its interior, is denied to him. But the station is all interior … [.]

In this passage, Theroux makes a very human mistake; he sees his own, limited experience as universal. Because access to village life is unavailable to him, he tells us that meaningful interactions with rural India are off-limits for all foreigners. And he pulls off a neat trick in the process; because non-Indians cannot reach the “real India”, he implies, his deductions from life on the Amritsar Station platform ought to provide sufficient insight to his audience.

(Image credit: Independent)

What does he find on the platform? A group of people, “very black, thin, with small sharp teeth and narrow noses and thick glossy hair. … They were spitting, eating, pissing, and strolling with such self-possession that they might have been in a remote village in the deepest Madrasi jungle… [.]”

And this represents the greatest challenge that we find throughout The Great Railway Bazaar. Theroux writes a cracking good yarn, but his bold descriptions of the people of India could as easily have been culled from an 18th-century British anthropological compendium as this 1970s travelogue. Bengalis, “whose complexion resembles the black goddess of destruction they worship,” are “nimble at boarding trains.” Sikhs exemplify virtues of “piety, ferocity, and strength” but are, he reports, believed to be simple “yokels”.

Tamils – and Theroux returns over and over again to the darkness of Dravidian skin – “[A]re black and bony; they have thick straight hair and their teeth are prominent and glisten from repeat scrubbing with peeled green twigs.” Another (adult) Tamil man has “the look of the feral child.” When writing of Adivasis, Theroux quotes his guidebook: “black skin”, “flat noses and thick lips”, “serpent worship”. We should, perhaps, not be surprised that when one tries to understand one of the world’s largest and most diverse nations from the inside of a train, the results trade in stereotypes and crude racism.

When Theroux does describe conversations with the Indians that he meets on the train, he seems to have had only two types of interactions; Indians are depicted as either credulous mystics (he is told about reanimation, a sadhu who communicates with monkeys, a yogi who predicts the future) or fools to be dispatched with one-liners that are only half as clever as Theroux imagines them to be (“Had any success lately?” he jibes at the government employee who works in drought prevention).

When my mother tried to defend our guesthouse cook, her misunderstanding was born from good intentions paired with an idea of employment that involves offices and fixed hours and wage rates and sick days. But the impact of her good intentions was small; we weren’t hungry when our next dinner came around. Our cook left work early one night.

But foreigners on the subcontinent have a way of bollocking up the very people we try, in our ignorance, to help. My family’s next good intention likely counteracted the first; guilty about their lack of appetite at dinner, they asked to have the meal packed for the next day.

They likely hadn’t noticed that the cook and his family ate our leftovers after every meal. In their effort to avoid offending the cook, they inadvertently deprived him and his family of their dinner. Chastened from my earlier intervention, I said nothing. A week later, I reflected on this moment as my mother caused a traffic jam at Siolim Junction by patiently yielding to oncoming traffic before making a turn. Eventually, a policeman yelled at her.

“Are you mad?” he shouted. “Just go!”

(Image credit: Navhind Times)

In his own way, Theroux’s intentions are also good. But, by and large, he is trapped in the white man’s conceit that the best way to learn about a thing is to ask another white man. As he dribbles bits and bobs of his reading list through The Great Railway Bazaar, we are confronted with the greatest hits of the British colonial era: Kipling, Maugham, Joyce, Forrester, J. J. Aubertin. The sole Indian text mentioned by Theroux is Autobiography of a Yogi. It may be no great surprise, given his reading list, that Theroux finds fools or mystics in almost every meeting he recounts.

The same cannot be said for V. S. Naipaul. A Trinidadian of Indian extraction, in An Area of Darkness, Naipaul recounts his first trip to the country of his ancestors, embarked upon at the age of 29, a resident of the United Kingdom and a rising star in the literary world. Naipaul occupies a special status. He is Indian but foreign. He also shares the history of former British colonial subjects but is now a resident of the imperial nation that has shaped India so fundamentally. Whereas Theroux seems to see an India filtered through the lens of her erstwhile coloniser, Naipaul sees a palimpsest, the India that confronts him written over the India of the British Raj, written over the India of his grandfather, hints, and memories of each visible across time.

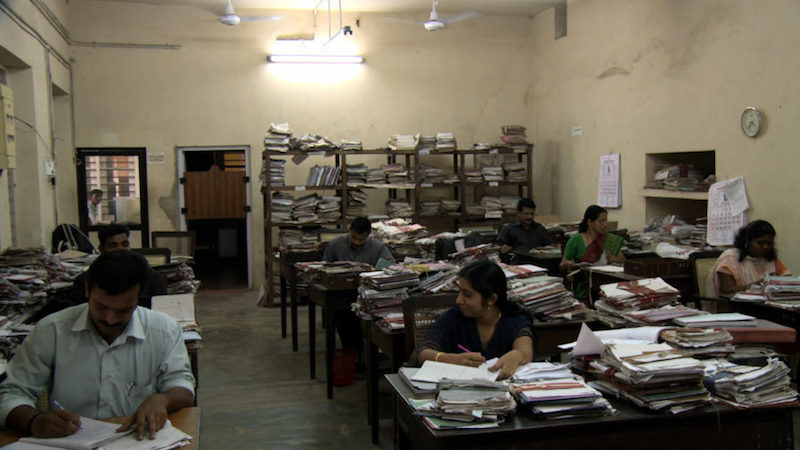

Naipaul’s first stop in India is the Bombay Customs House of 1962. Few foreigners are able to speak at length about India without an anecdote of painful bureaucracy; ask my mother about her trip to the Indian visa processing centre. But the almost obligatory narrative is keenly captured by Naipaul. Where Theroux would only see idiocy and slavish obedience to foolish procedure, Naipaul hints at an understanding that procedures that appear foolish to him may have their own logic. When Naipaul’s companion faints in a hot Bombay government office, Naipaul approaches hysteria as a clerk, dispatched for water, returns to the office empty-handed:

His eyes distastefully acknowledged my impatience. He neither shrugged nor spoke; he went on with his papers.

It was worse than impatience. It was ill-breeding and ingratitude. For presently, sporting his uniform as proudly as any officer, a messenger appeared. He carried a tray and on the tray stood a glass of water. I should have known better. A clerk was a clerk; a messenger was a messenger.

Naipaul sees India with two sets of eyes. One sees absurd procedure interfering with the task of getting water to a fainted woman. The second is embarrassed because it has overlooked the delicate balance of responsibility at work around him in the Customs House.

(Image credit: Sirf News)

But Naipaul is painfully aware of this bifurcated vision. “For the first time in my life,” he writes of his arrival in India, ”I was one of the crowd. … [I]n Bombay, I entered a shop or a restaurant and awaited a special quality of response. And there was nothing. It was like being denied part of my reality. … I might sink without a trace into that Indian crowd.”

Gravitating to those who share similar experiences, Naipaul writes of a European educated Bombay engineer who has returned to the city of his birth. “By the standards of London, he was well off. By the standards of Bombay, he was overprivileged. But he was miserable. European engineers less qualified than himself earned three times as much for their services as experts and advisers.”

But even as Naipaul, writing only 15 years after Independence, lays bare some of the scars wrought by colonialism, he seems ignorant of the ways in which it may have touched his own life. Naipaul, having moved from the Trinidad of his birth to London, is now a conspicuous outsider who awaits that “special quality of response.” Finding himself awash in a sea of Indian faces, he is stunned to no longer stand out.

The post-colonial theorist Frantz Fanon, writing of a young man who had recently returned home to Martinique after living in France, highlights the challenge of maintaining coherent identity after being submerged in the culture of one’s coloniser; “He no longer understand the dialect, he talks about the Opera, which he may never have seen except from a distance, but above all he adopts a critical attitude towards his compatriots. Confronted with the most trivial occurrence, he becomes an oracle. He is the one who knows.”

Having spent years trying to remove from himself the qualities which identified him as a man from Martinique, Fanon’s example finds himself outraged by ways of being that had once come naturally to him.

For those of us who haunt the drinking holes of Lower Parel, Lodi Colony, or Indiranagar, this character is commonplace. He casually peppers British slang into his speech. She’s suddenly developed flat American vowels. They both throw fits when toilet paper can’t be found.

But traveling across India, Naipaul, seemingly unaware, casts himself in this role. “Indians defecate everywhere,” he writes. “India,” he tells us, “will never cease to require the arbitration of a conqueror.” Describing India and her culture, Naipaul uses the adjective “medieval” seven times in 30 pages. He compares a diminutive government monument to “Indians on a dancefloor; they are attempting attitudes which do not become them.” With each of his many attacks, he reminds us firmly that India is the backward other. And, by extension, that it doesn’t really form such a big part of him.

Nowhere else is this more apparent than in Naipaul’s treatment of caste, which preoccupies him with the same intensity with which Theroux approaches skin colour. Caste is, to the atheist Naipaul, a superstitious abomination that constrains the subcontinent. Quite right. But his obsession with the perceived Indian obsession with caste permeates the text.

“They were a brahmin family and their vegetarian food was served according to established form. No one was allowed to touch it except the dirty old servant. .. With the very fingers that a moment before had been rolling a crinkled cigarette … he now – using only the right hand, of course – distributed puris … [.] He was of the right caste. Nothing served by the fingers of his right hand could be unclean; and the eaters ate with relish.”

In the opening pages of An Area of Darkness, Naipaul writes of a childhood in which he would refuse to share food with his non-brahmin, non-Indian classmates. But by the time the book reaches its midpoint, Naipaul seems to believe that his rejection of caste means that caste no longer impacts his life. White people, brahmins, and men like to believe things like this.

In doing so he echoes Theroux in his train car, surrounded by South Indian businessmen’s complaints of North Indians’ unwillingness to speak English, oblivious to the fact that his presence might influence the conversations that take place around him. But Naipaul’s roots are U.P. brahmin; that this influences his interactions remains a blind spot even as he chastises those around him for the illogic of their beliefs. His intentions pure, he is depriving the cook of dinner in an effort to avoid giving offense.

(Image credit: Supporting Dalit Children)

All my mother wanted was to be nice to the poor old man who was making delicious food for us. His boss – another character that we’ve all met before – had texted to tell us that we shouldn’t tip too much because the cook would spend it all on booze. Maa was upset at the implication that only rich people had earned the right to get drunk.

And her intentions, even when they backfired, were admirable. Perhaps more admirable than those of Naipaul, who finds himself so occupied in differentiating his own identity from his Indian past that he almost compulsively attacks the society and culture that he also treasures and, mostly, understands.

His intentions are no doubt more admirable than those of Theroux. The points he scores for effort, for prose, and for originality are more than erased, if not for his claim that all of India can be understood by a lone railway platform, then for his sardonic and occasionally cruel take on India. For the casual punchlines that he crafts out of child sex workers and the immolation of Dalits.

We read the travelogues of foreigners because the foreigner is able to capture the novelty in ways of living that are routine to the citizen. Americans learned of their own nation from the observations of French De Tocqueville. Paris was described to much of the world in the prose of 20th-century American novelists. Today, BBC presenters narrate perfect English tales of new musical genres in England’s former colonies; Radio France Internationale does the same for those of France.

But when we read these travelogues, we must also read them as artefacts of the preconceptions their authors carry with them. In Theroux, we see an idea of India mediated by centuries of colonial writing. In Naipaul, we see a struggle to maintain a sense of self that is distinct from India in the midst of the competing pressures of Indian, Trinidadian, and British identities. We must not do away with the foreigner’s travelogue, but each must be read with a keen awareness of each set of eyes with which the author is seeing.

Have you read these books? Do you agree with Kerry’s critique? Share with us in the comments.

Kerry Harwin

Kerry Harwin is a Goa and Delhi-based freelance journalist who focuses on marginal communities and the post-colonial experience. You can regularly find his work in GQ India and you can find his images and musings, along with a healthy dose of Marvin, his pink monkey friend, at @flashhardcor on Instagram.

Photo Credit: Polina Scharpova

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!