Feature

The Wondrous World Of Wordless Picture Books

As I walk through the aisles of a bookstore, I fall in love ever-so-often. A stunning cover, an intriguing blurb, or even an enticing first page has the potential of drawing me into a relationship that could last for a long or short period of time.

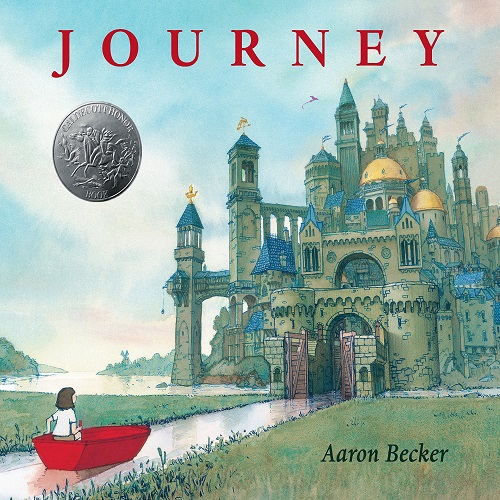

One such amble led me to a children’s book that sparked a long-lasting love affair. It told the story of a young girl who escapes from a lonely reality into magical worlds – into enchanting forests, magnificent castles and soaring skies peppered with fantastical aircrafts. She literally draws herself into these worlds as her red pencil deftly sketches doors, boats and hot air balloons that allow her to escape the mundane.

This book was Aaron Becker’s Journey. This is a book where pictures, rather than words, tell the story. For me, it was the first step into a whole new world – the rich, varied, immersive world of wordless picture books.

An Artist’s Vision

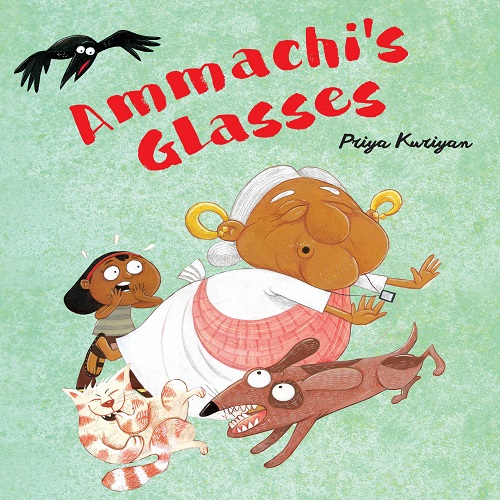

Despite the lack of text, a wordless picture book follows all of the basic requirements of a book – it has a plot, narrative structure, character development, etc. In addition, it possesses a unique identity that is driven by an artist’s vision. Some artists use mouth-watering water colours to tell their stories such as Wave by Suzy Lee. Some use humour, like Priya Kuriyan’s Ammachi’s Glasses. Some open up windows to boundless imagination like Flutterfly by Niveditha Subramanium and Free Fall by David Wiesner. And some use cut out diorama-type illustrations such as Canato Jimo’s Snip, the adorable story of a haircut gone wrong.

These books are exciting because of their universal appeal. Madhumita Srivastava, art educator and illustrator of wordless picture book The Little Red String, believes that children respond instinctively to pictures. We have told stories through pictures on the walls of our temples and the stained glasses of our churches for centuries. The wordless picture book has the same universal appeal unencumbered by language, age and region, thus drawing all kinds of children into their magic.

Co-creating Unique Reading Experiences

What draws a child to a book like this? A good book, Srivastava says, among other things, takes you away from your mundane reality into another more exciting one. ‘A wordless picture book takes you even beyond into a whole new level of reality,’ she says. This unique reality is experienced when the reader interacts with the pictures. The process of reading is a curious alchemy between the author and the reader. The readers bring their own imagination and experiences to interpret a space suggested by the author.

This process is enhanced further in wordless picture books. By opening the pages of such a book, children fall headlong into a story that requires them to provide context and cues from their own imagination and experiences to move the story forward.

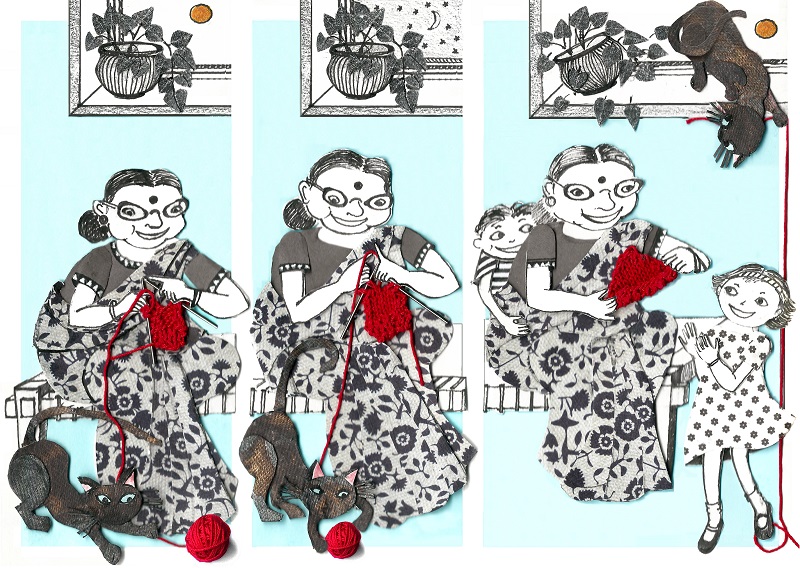

Take The Little Red String, for example. It is the story of how a left-over piece of red wool opens up a world of possibilities for children (and a cat) at play. But, a closer look at the pictures also give you an insight into the family and its dynamics. Srivastava has done many workshops with children and has seen the story being interpreted in different ways each time. This is because children end up bringing in their own background, visual understanding and imagination to the table.

(Image via Storyweaver)

The Fascinating Art Of Visual Storytelling

For children who respond to the visual and enjoy art, these books are a particular treat. Apart from the sheer range of artistic styles, there is joy in the nature of visual storytelling. The ability of the artist to express complex ideas, characterisation and emotions through pictures is a fascinating thing to see. For example, Ammachi’s Glasses tells the story of a grandmother who has misplaced her glasses and the ensuing misadventures. The pages are rich with visual clues that not only create the character of absentminded Ammachi and her amused family, but also the setting – a middle-class household with its quirks that children will relate to.

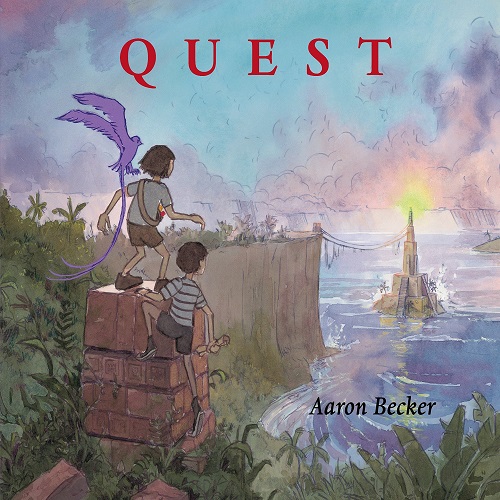

In Aaron Becker’s Quest and Journey, the artist uses the red pen as the narrative device. In Istvan Banyai’s Zoom, the stories are told through pictures within pictures and landscapes within landscapes, making the discovery of each layer endlessly fascinating for both children and adults. In a good wordless picture book, the reader finds something new every time they look at the pictures.

Helping Reading Literacy

The focus on art and the absence of text often misleads parents and teachers into thinking that these books offer little to traditional reading literacy. Heeru Bhojwani, Information Curator and Coach at the American School of Bombay, begs to differ. She tells me that wordless picture books have a huge role to play in the development of reading and literacy. ‘It depends on if you want to raise a reading child or a thinking child,’ she says.

If the latter, wordless picture books offer children the opportunity to exercise critical thinking skills and their imagination – both of which are fundamental to reading literacy. Since every wordless picture book has a structure, children have to use skills such as sequencing, prediction, drawing conclusions based on experiences, etc. to make sense of the story. The format also allows children to expand their creativity. Since there are no words, children feel free to make up the story as they like, and even change the ending, if they wish.

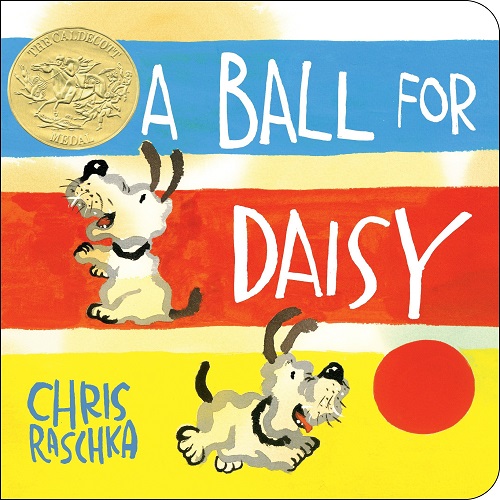

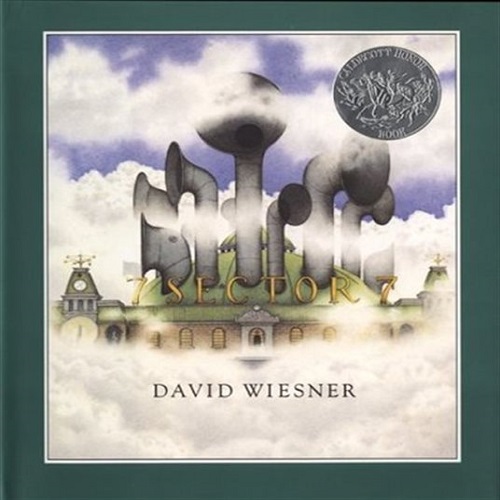

Bhojwani also adds that there are wordless picture books available for those up till the sixth and seventh grade, and has several suggestions for these. Younger children can enjoy the simpler structure of books like A Ball For Daisy by Chris Raschka, a charming story about Daisy the dog and the ball she loves, and Sector 7 by David Wiesner, an award-winning pictorial story of a boy who befriends a cloud on top of the Empire State Building. Books for older children explore a whole range of complex themes and topics from friendship and loss (Robot Dreams by Sara Varon) to migration and rebuilding communities (Belonging by Jeannie Baker and The Arrival by Shaun Tan). Another genre that finds expression in wordless picture books is the travelogue, beautifully represented by Anno’s Spain by Mitsumasa Anno.

Conclusion

For parents and children looking at these books together, Bhojwani suggests some fun activities. Take copies of the pages, jumble them up and ask your child to put them in order (the order might not be the one in the book, but that’s fine). This is a game that helps with story sequencing and imagination. To help improve observation and interpretation skills, try a treasure hunt of the elements in the books or use a spread as a writing prompt.

Srivastava’s suggestion is to start with the child. She lets her daughter take the lead in narrating the story as it unfolds for her when they read together. This leads to all kinds of explorations of the narrative by finding new meanings and connections. They particularly enjoy reading books like Kaori Takahashi’s Knock Knock and Deepa Balsavar’s Round And Round Books since they are physically structured to allow for a flexible story experience.

This, in fact, is the essence of wordless picture books – they can become anything you want. Just like the protagonist creates his/her own world with a crayon in Harold And The Purple Crayon and Magpie Magic, Srivastava believes picture books give children the confidence to create new things. ‘They give a child the confidence to feel that if you can imagine it, it can exist,’ she says. Certainly a good thought – the kind from which springs the best of human creation, from art to scientific discoveries.

Lubaina Bandukwala

Lubaina Bandukwala has been in children’s publishing as a writer, editor and festival curator for a decade. She founded the Peek A Book Literature Festival for children, which is now in its fourth year.

Read her articles here.

Check your inbox to confirm your subscription

We hate spam as much as you hate spoilers!